Neurotechnology: Much More Than You Wanted to Know

What We Know Now (2024)

I have never met you, yet I can guess what you look like.

I know, because that’s what I look like, too.

Part 0: Why did I write this?

I wrote this post for myself.

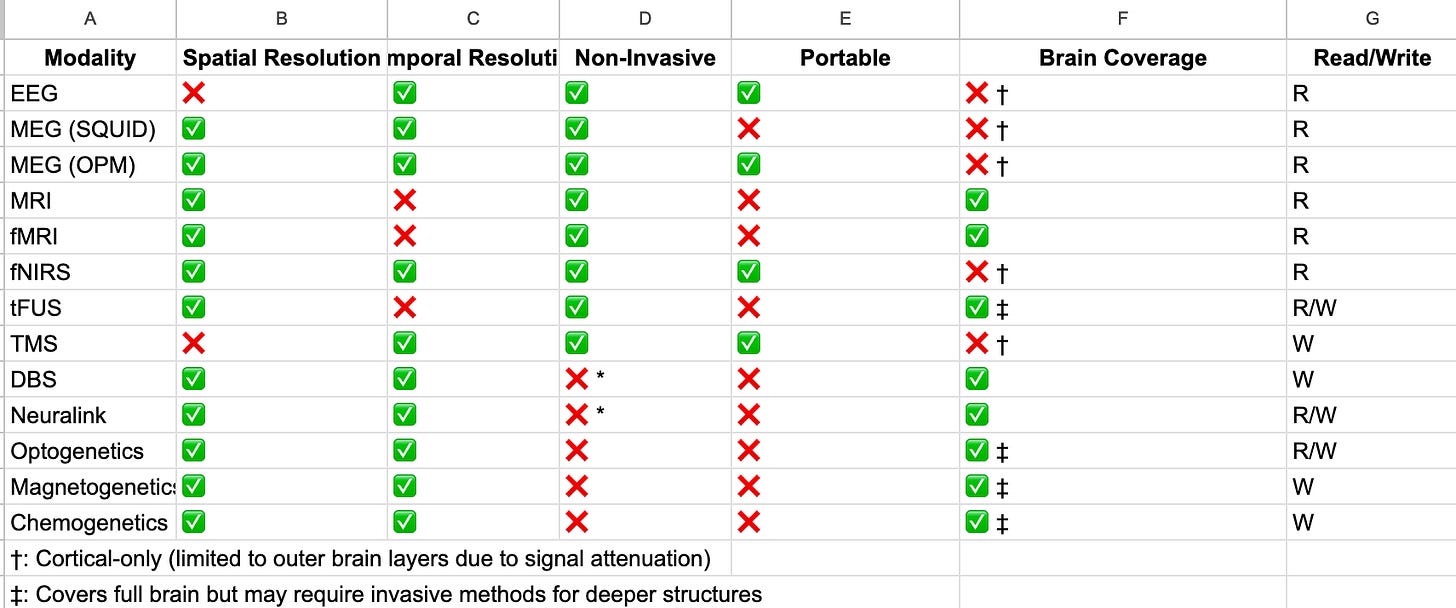

I want to understand how the brain works. Everytime I go out to do so, I get hit by terms like MEG, fMRI, transcranial. This post is my attempt to make sense of the brain.

I’m excited in particular about neurotechnology, the ways in which we’ve figured out how to see inside the brain (neuroimaging), and modify it (neuromodulation).

In Parts 1-3, I go over the current state of the technology, and in Part 4, we dream of ways to make them better.

Every human being’s lived experience is mediated entirely through the brain. If we could mechanistically understand the brain, we could build a panacea for any malady of the mind. To cherry-pick: Alzheimer’s, depression, PTSD, anxiety. These are the tip of the iceberg. We could also enhance our minds, to be self-aware, loving, empathetic.

By the end of this article, it’s my hope that you’ll understand way more neuro jargon than you did going in.

This post is indulgent. Some sections are marked with the prefix “Nerdsnipe: ” If you find that you’re not as intrigued by the ins and outs of some section, skip it.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Neuroscience

Part 2: Neurotechnology

Part 3: Applications

Part 1: Neuroscience

What is a neuron?

First, let’s talk about the structure of the brain.

The brain is made up of two types of cells (building blocks):

Long boys (neurons)

Spiky boys (glial cells)

Glial cells play a supporting role in the brain. Neurons play carry.

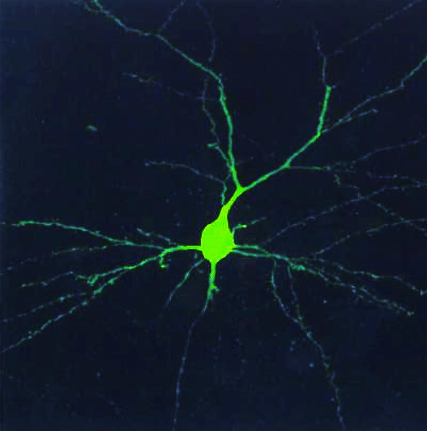

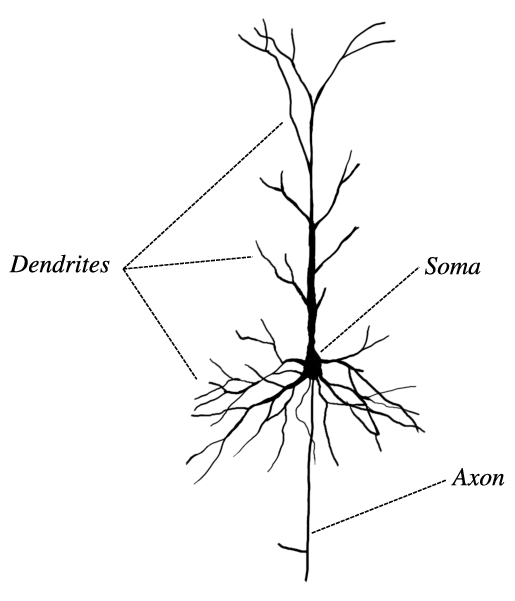

Here’s an image of a neuron:

The long component is an axon. The length is important for electrical signals to travel between neurons.

The branch-like components are dendrites.

In summary:

Output channel - axon. Through its axon, the neuron sends an action potential

Input channels - dendrites. Through its dendrites, the neuron receives post-synaptic channels

Junctions - synapses

Action Potentials

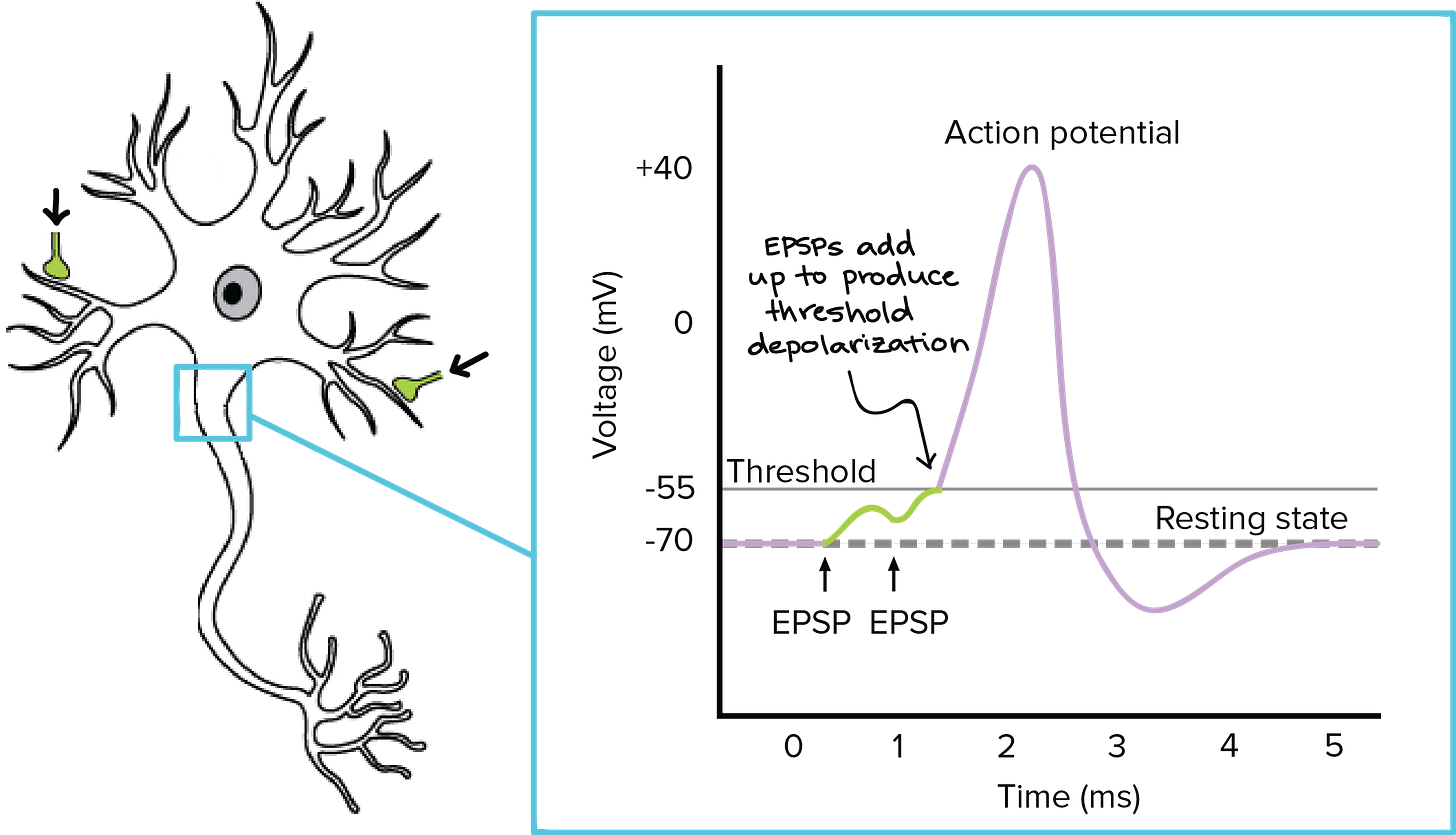

Electricity travels from one neuron (pre-synaptic) to another (post-synaptic). Note that pre-synaptic and post-synaptic are labels that depend on your frame of reference. The post-synaptic cell in the image above in turn generates an action potential for another neuron, acting as its pre-synaptic cell.

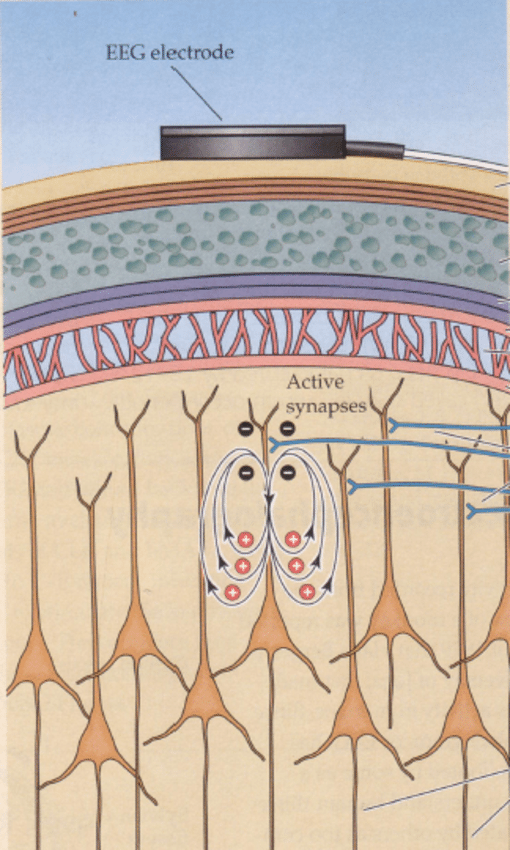

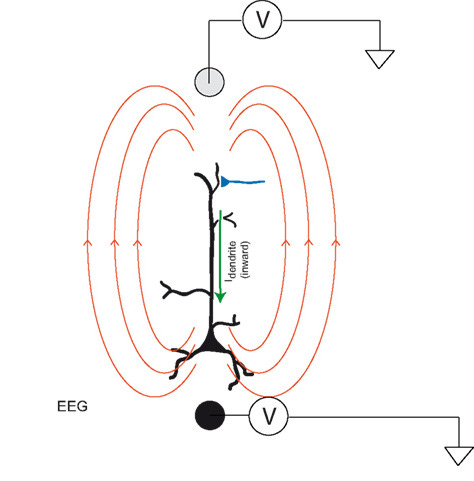

The action potential of a single neuron is hard to detect via non-invasive methods. But the sum of thousands of synchronized post-synaptic potentials is perfect for EEG.

As shown in the figure above, if the threshold for detection is exceeded, we get an action potential.

Note: this summation can be either temporal (same time, slightly different locations) or spatial (same location, slightly different times).

Networks

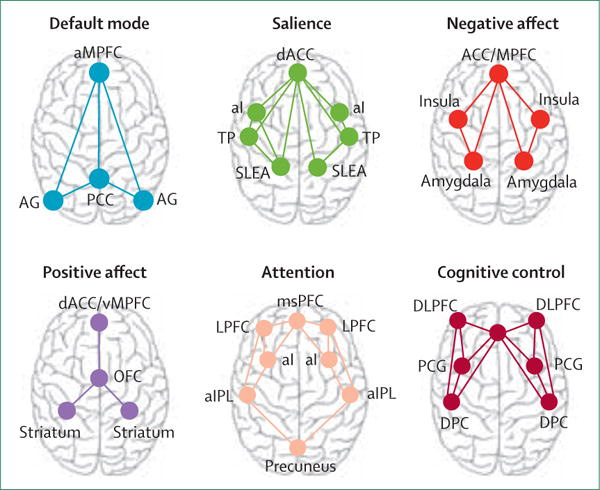

Moving beyond the neuron as the atomic unit, thinking of the brain as an interconnection of neural circuits.

Which regions are active when you’re doing nothing?

What about when you’re paying attention?

Imaging (primarily using fMRI) has allowed us to build some understanding of these circuits.

(Side note: there’s an analogy in mechanistic interpretability of deep learning models — going from neurons to circuits )

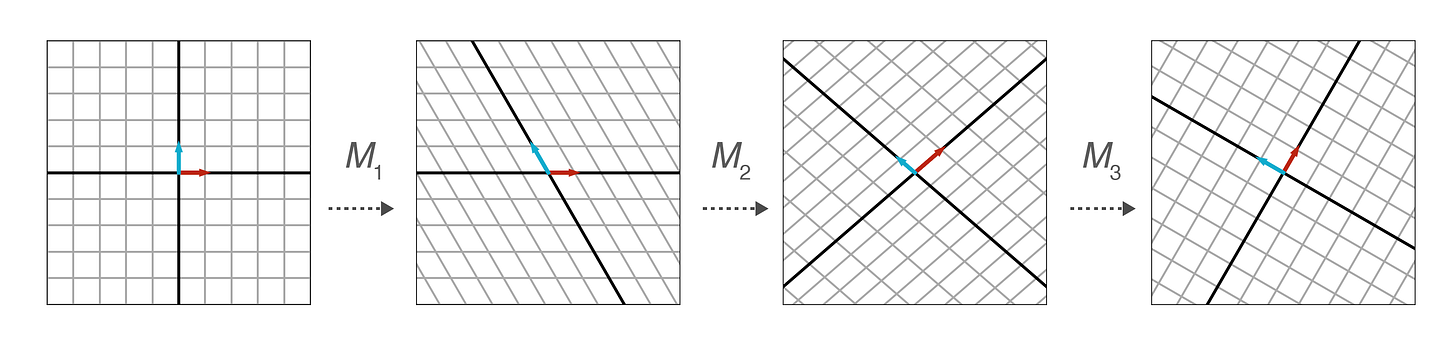

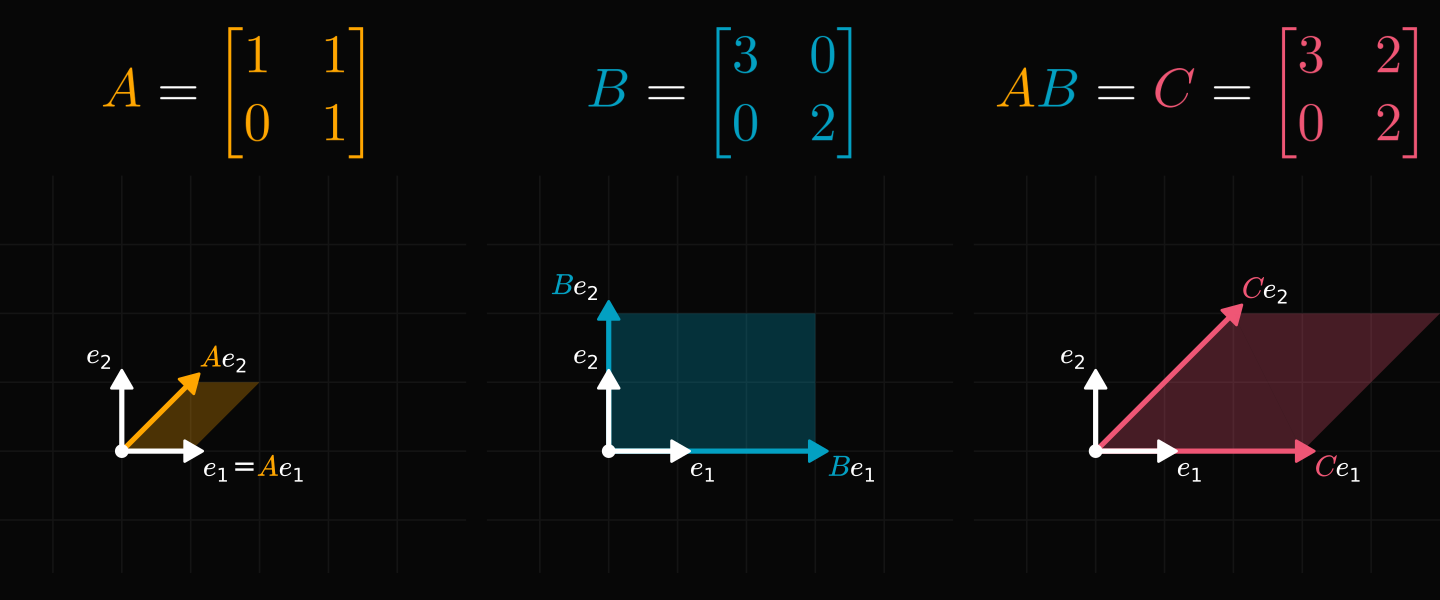

Let’s talk about maps. Matrices let us reshape space.

In the picture above, notice how we’re just moving lines around. A matrix is also called a linear map. The study of matrices is called linear algebra.

But matrices are also unwieldy.

Eigenvalues are a really useful notion that pop up all the time in linear algebra.

An eigenvalue (\lambda) does the same thing as a matrix, but it’s a scalar. Much nicer to work with.

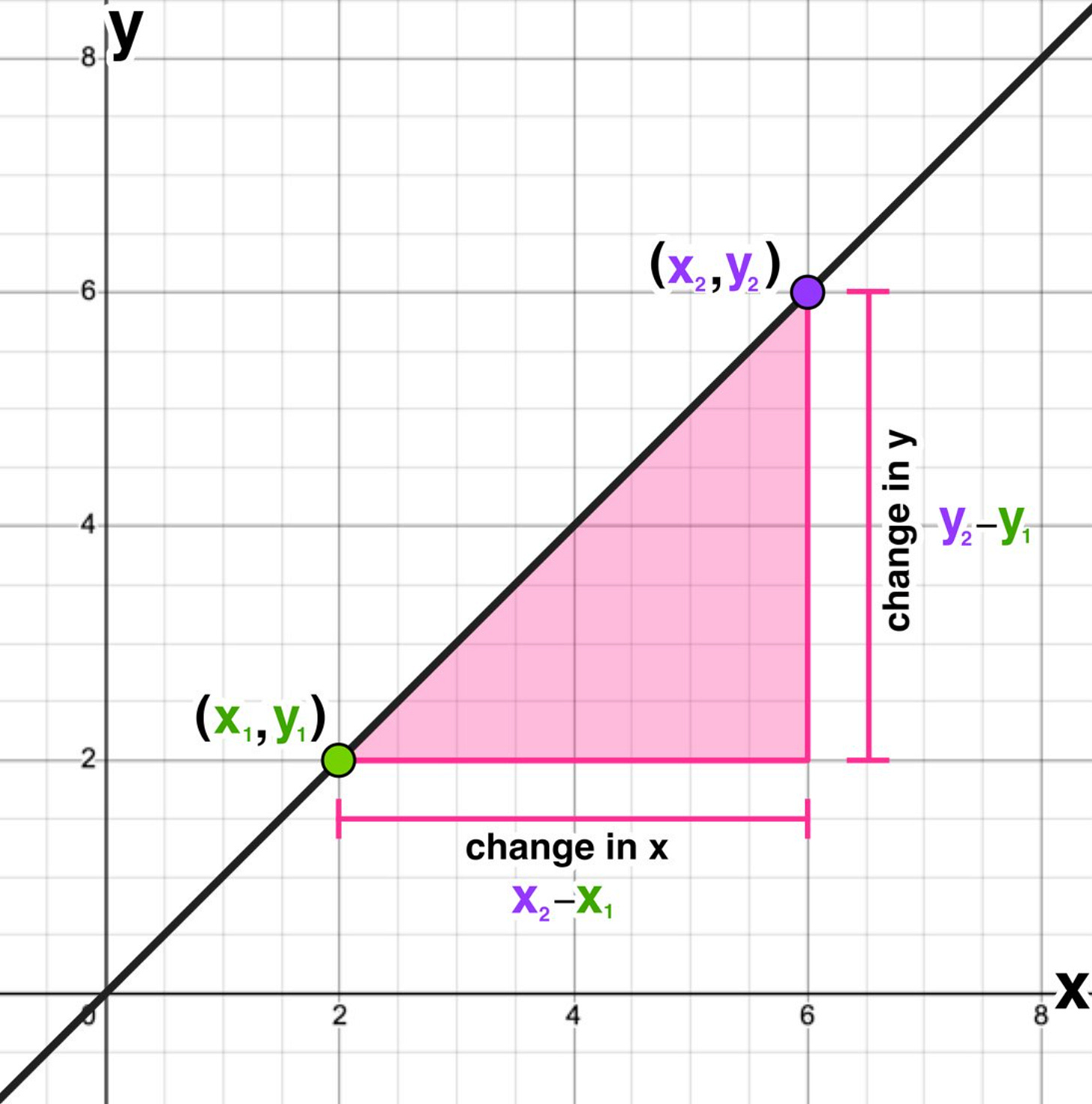

We are used to thinking about waves temporally. How does a wave change over time?

But in studying brain networks, we are more concerned with their spatial evolution.

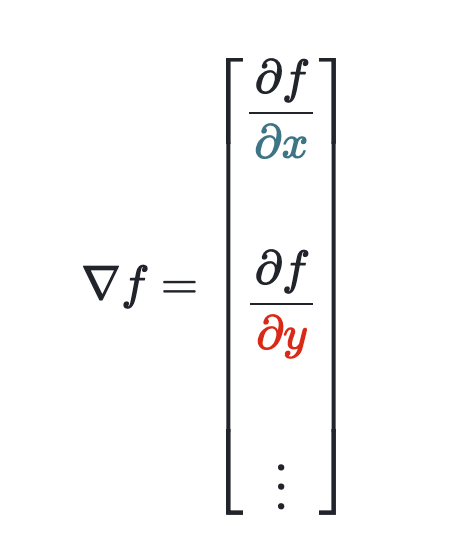

First, we take a derivative. x, y, … are spatial coordinates.

This gives us a vector of partial derivatives.

But we don’t really care about the direction of the waves.

We care about the curvature.

Here’s a fun little exercise. Try drawing a bunch of tiny lines, going in whatever direction, and see what shape it forms.

The change in the change is the curvature.

This is the second derivative.

Now we want a clean number to describe the entire wavesystem, not a vector with one element for each dimension.

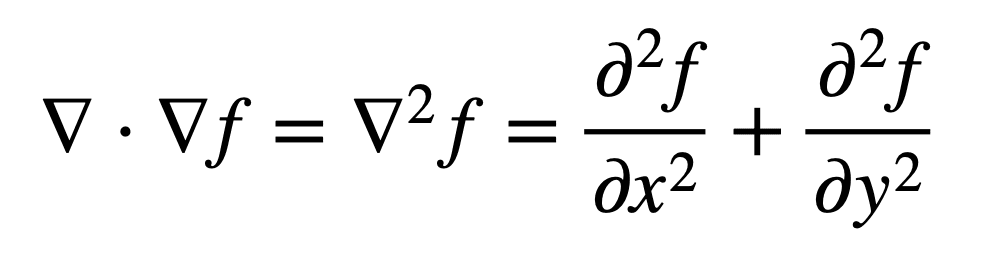

So we take the div of our grad from earlier:

Voila, we now have the Laplacian.

The Laplacian allows us to describe the wavesystem with a singular number.

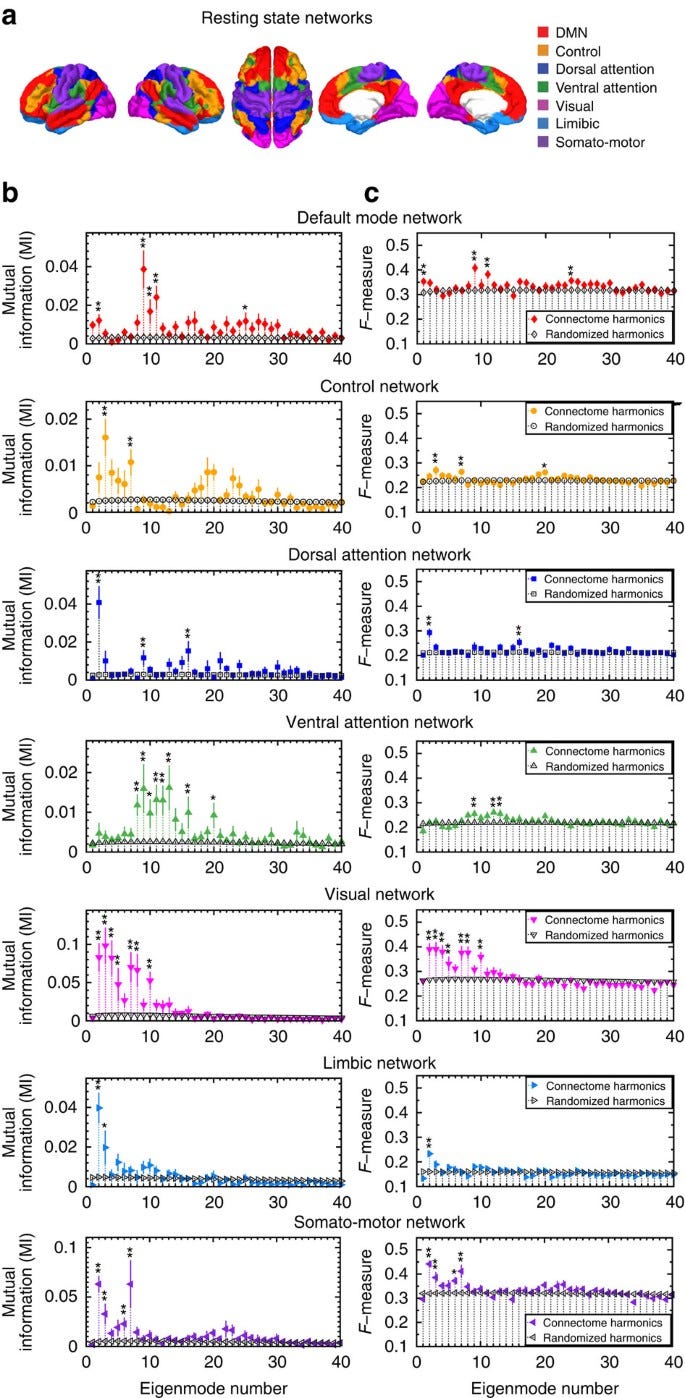

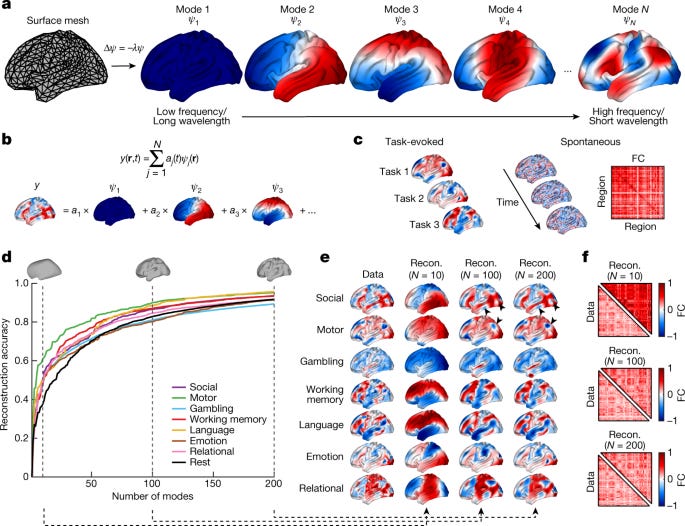

If the brain has resting state networks, we should be able to decompose the connectome into these networks. Or, take the eigenmodes of the Laplacian.

That’s what Atasoy et al explore. They find that the 9th connectome harmonic is strikingly similar to the default mode network (top row in Figure below). Now, this is still early — the other networks aren’t as congruent. But it’s exciting to see evidence for a daring theory.

There is other research that instead looks at the geometric eigenmodes by Pang et al.

They get even better results.

This video is a great overview of both papers.

Neuroscience is nascent

We don’t really understand the brain all that well.

What if we built tools to interface with the brain?

Part 2: Neurotechnology

Electroencephalography (EEG)

Some neurons are easier to detect than others. It comes down to orientation.

Enter pyramidal cells. These cells are oriented perpendicular (it took everything in me not to use “orthogonal” here) to the surface.

EEGs can detect the electrical signals from pyramidal cells in the outer layers of the brain.

Recipe for an EEG electrode:

A metal (to conduct electricity from the cerebral cortex)

A conductive gel (a ‘bridge’ that makes it easier for the electricity to conduct)

A wire (for the electricity to travel through)

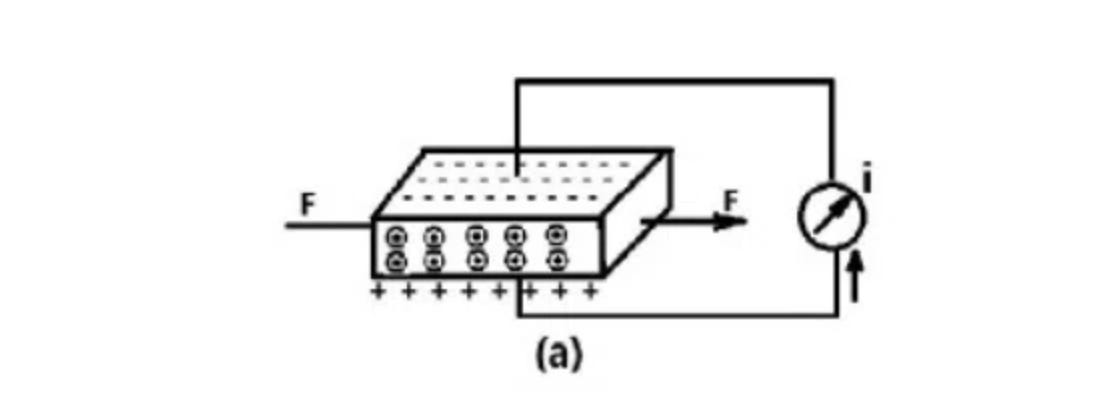

The EEG acts as a voltmeter in this circuit:

But EEG is low resolution and has poor spatial localization.

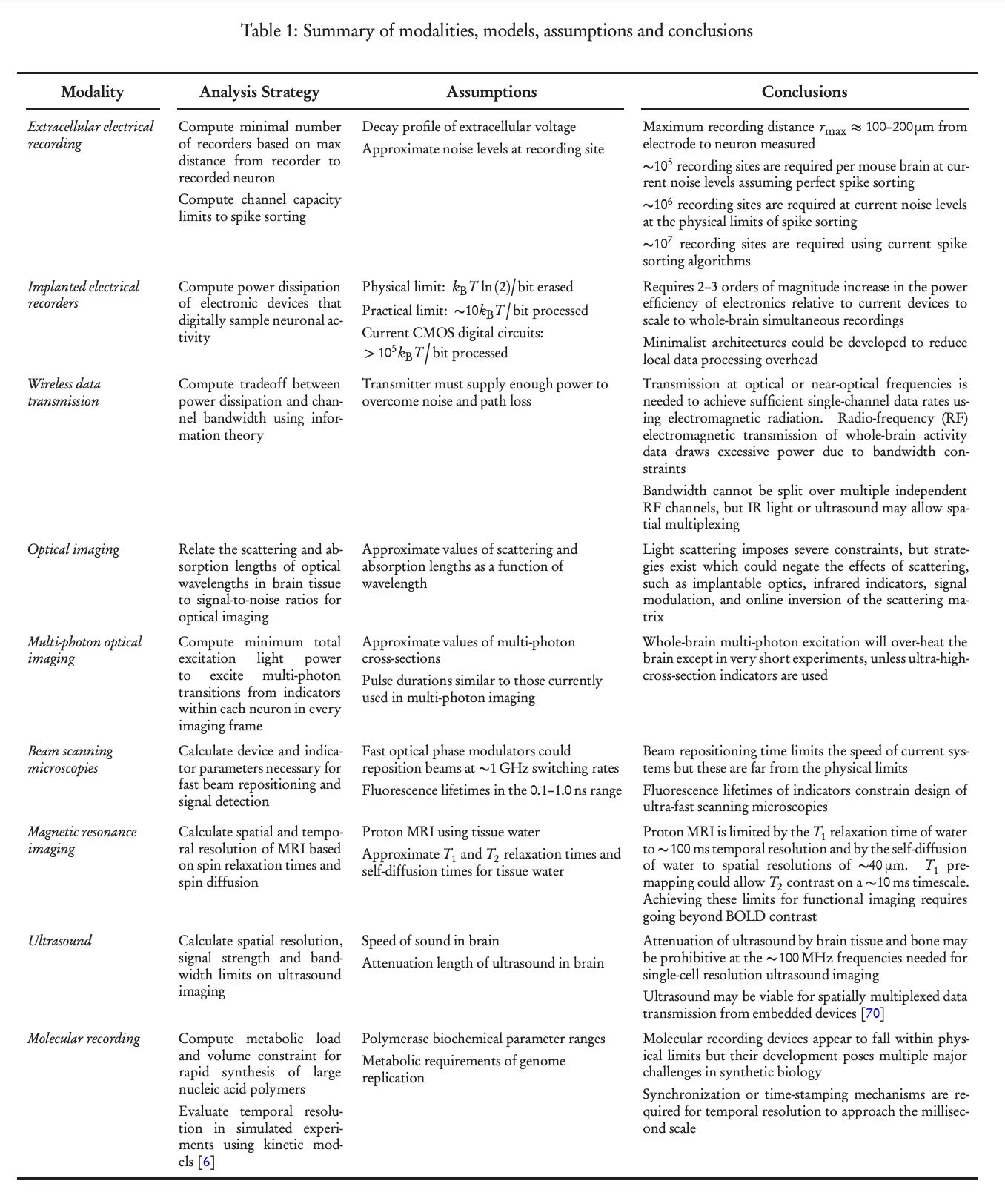

Advances in microelectronics could improve them. Here is a list of things that could be improved by Marblestone et al (2013), Section 4.14:

“Ongoing innovations in electrical recording that could be leveraged for dramatic scaling include the development of highly multiplexed probes, multilayer lithography for routing electrical traces,…, smaller electrode impedances to reduce the Johnson noise, amplifiers with lower input-referred noise levels, spike sorting algorithms capable of handling temporally overlapping spikes and adaptively modeling the noise...”

But I’m personally skeptical that any of these will be enough to make EEG a viable path towards BCI, at least by itself.

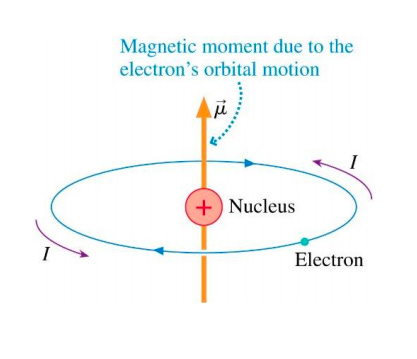

Wherever there’s electricity, there is also magnetism.

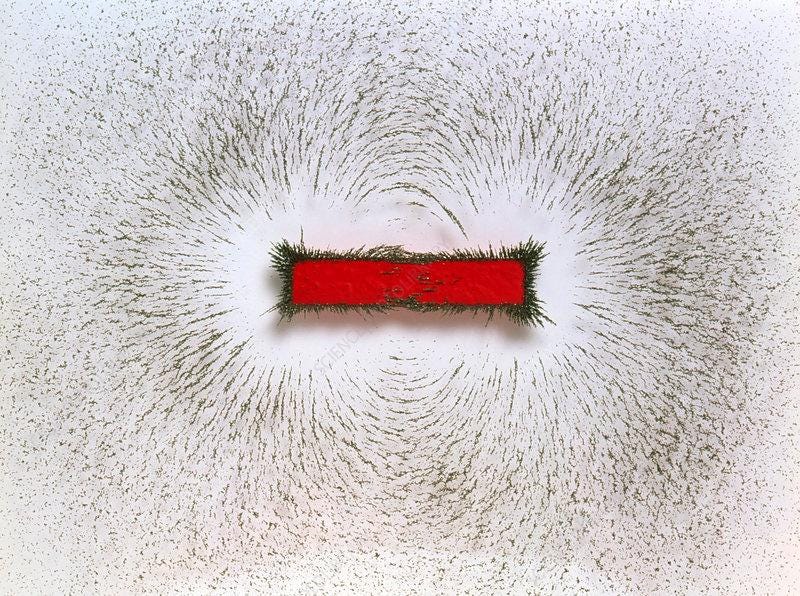

Nerdsnipe: Iron Fillings Experiment

Here’s a simple but cool experiment to figure out the shape of your magnetic field: scatter iron fillings and see how they orient naturally.

So the brain has an electric current, and that means it must also have a magnetic field!

Magnetoencephalography (MEG)

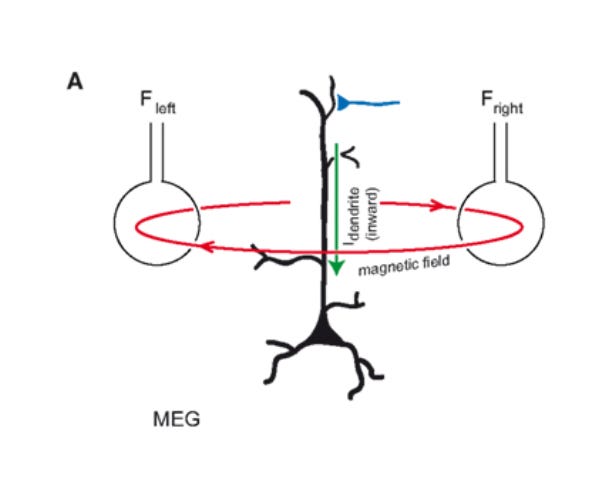

EEG is best at detecting signals perpendicular to the brain surface.

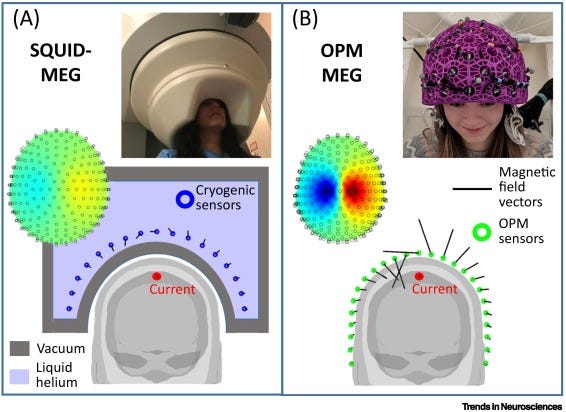

MEG, which detects magnetic field lines, is the perfect complement, and excels at measuring parallel signals:

Just like its electric current, the magnetic field of each neuron is tiny. We can measure the synchronized magnetic field of the pyramidal neurons. But how can we extend this to the rest of the brain?

SQUID-MEG

Enter SQUID.

SQUIDs act as a flux-to-voltage transducer, converting the hard-to-measure magnetism into an easily measurable voltage.

Back in the 1800s, this dude named Mike Faraday found that potential energy and magnetic field strength are related. While the E&M formula itself isn’t that important here, this is an important relationship to keep in mind.

Nerdsnipe: Josephson Junctions

Cool stuff happens when you cool matter to very low temperatures. Metals become superconductors, with zero resistance within their lattice. (visualization for intuition: lattice of moving atoms in an element goes from chaotic to stable). By Ohm’s Law (V=IR), there is no potential difference in this material.

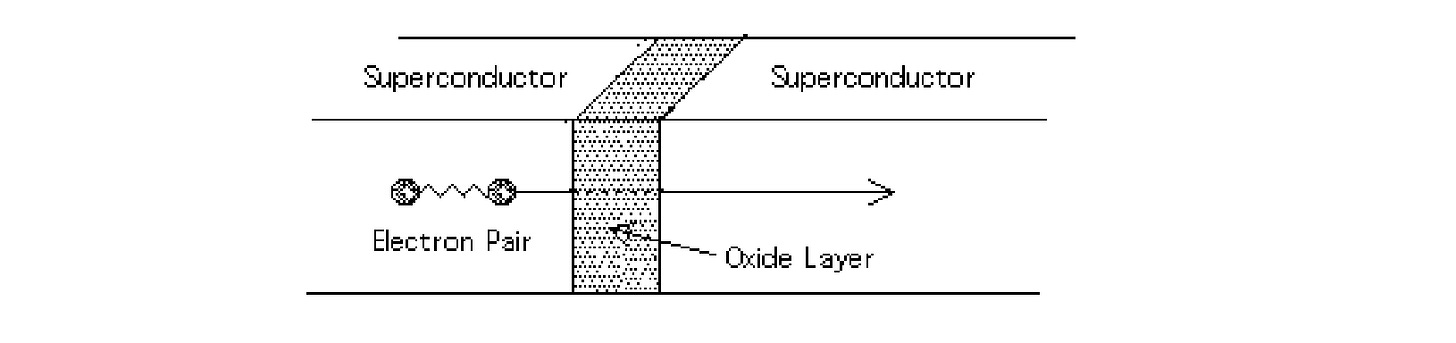

Now, what if we made a superconductor sandwich?

Something really interesting happens. Despite the thin insulating layer, the sandwich behaves as if there were no barrier. The electrons tunnel across the barrier.

This sandwich is known as a Josephson Junction.

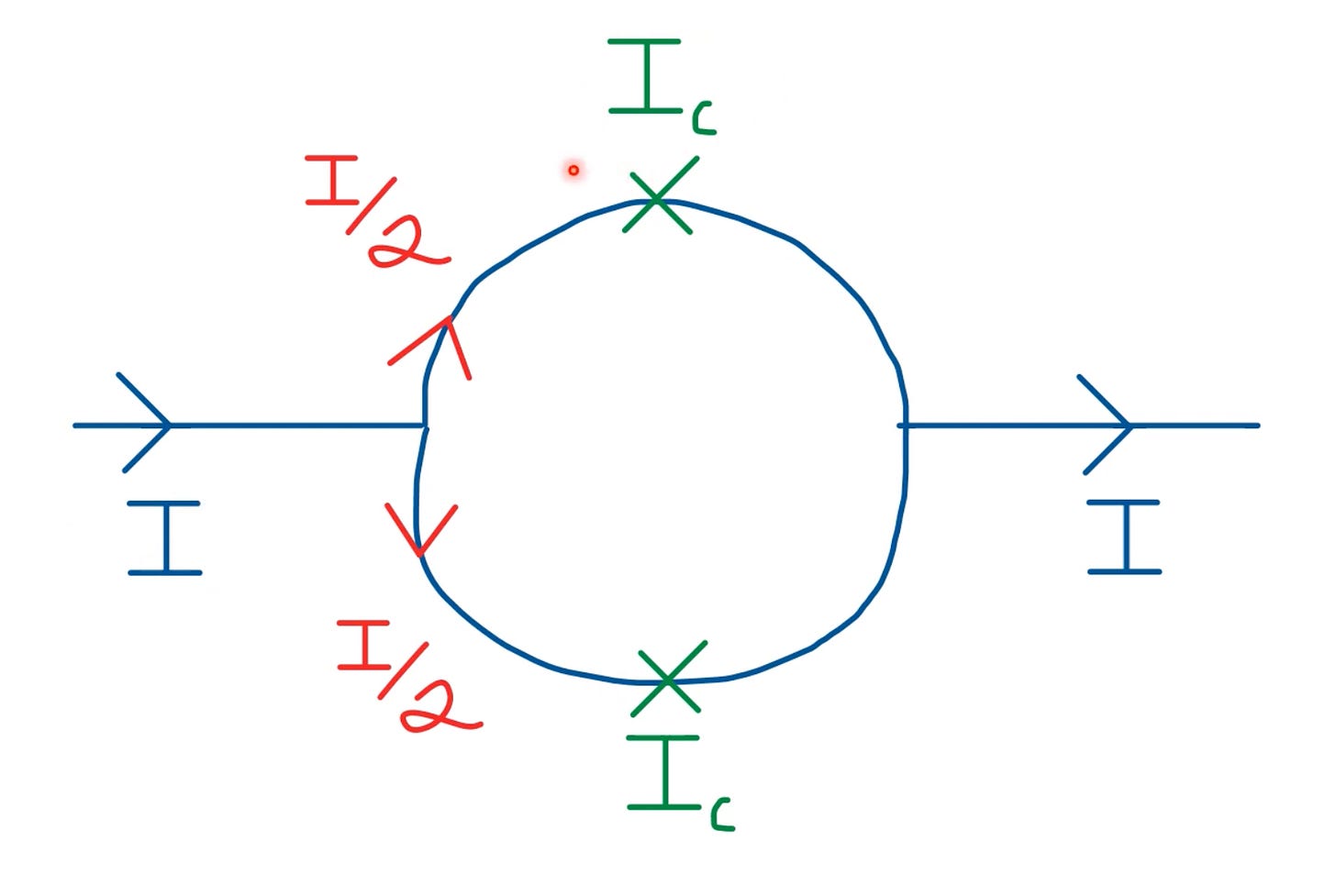

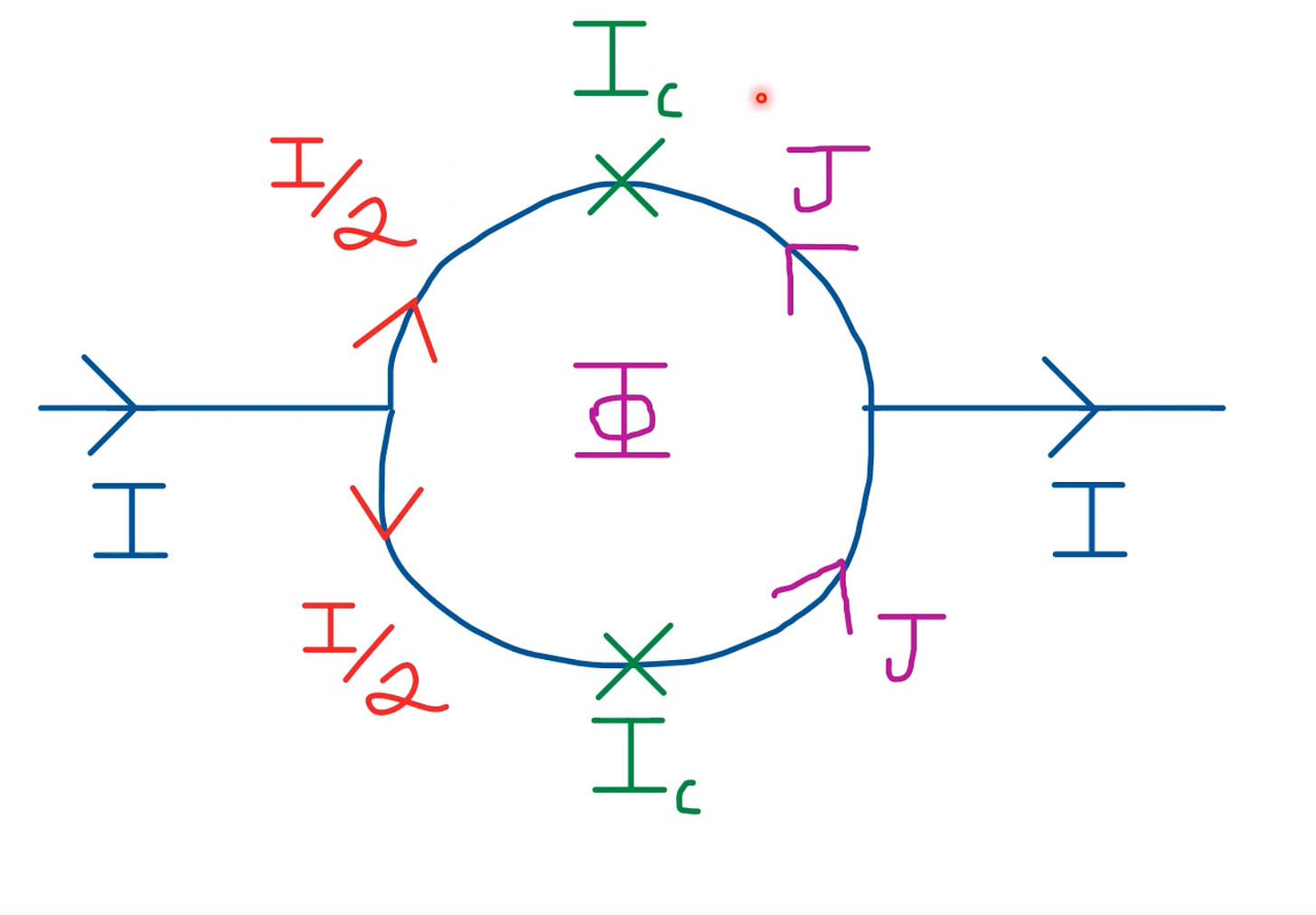

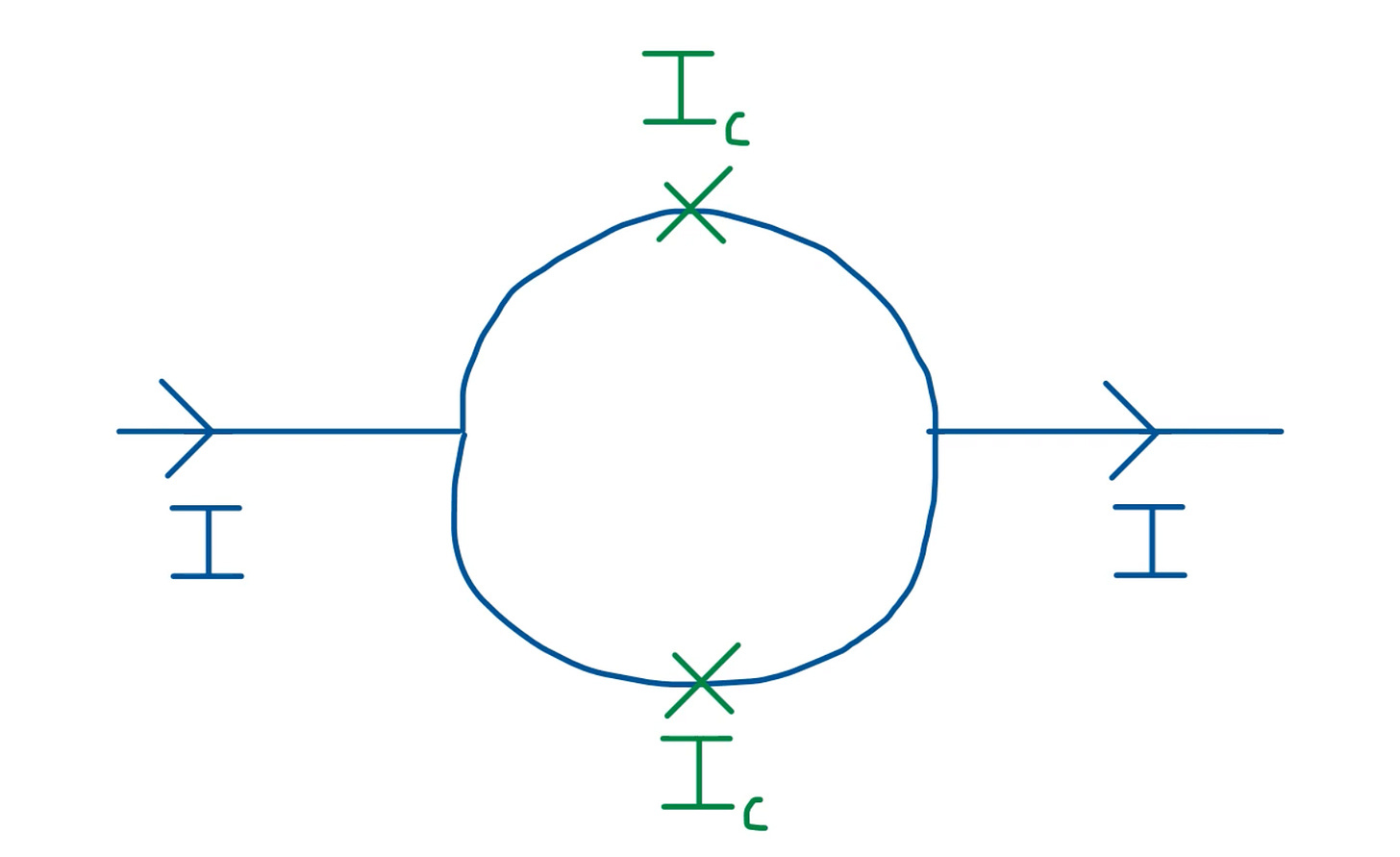

If we take two of Joseph’s male children and place them on opposing sides, we get a DC Squid.

Zero resistance is nice because SQUIDs have to be really precise to detect the minuscule magnetic signals of neurons. If we were to use room-temperature metals, heat dissipation and the like would overpower whatever faint electromagnetic signal is emitted by the actual circuit.

But zero resistance means zero voltage, and without voltage, we can’t measure the magnetic flux of the circuit.

It’s possible to induce a voltage in a Josephson Junction.

When we apply a biasing current, it splits into two currents - of the same magnitude but in opposing direction.

The induced magnetic flux in each part of the semicircle thus has a phase difference.

If we apply a current I < I_c, the junction behaves as if there’s no insulating layer. But for I > I_c, the junction experiences a small resistance, and in turn potential difference.

Abandoning constants, voltage depends on the time-varying magnetic flux:

I glossed over some details in my explanation above, see this paper for a detailed breakdown.

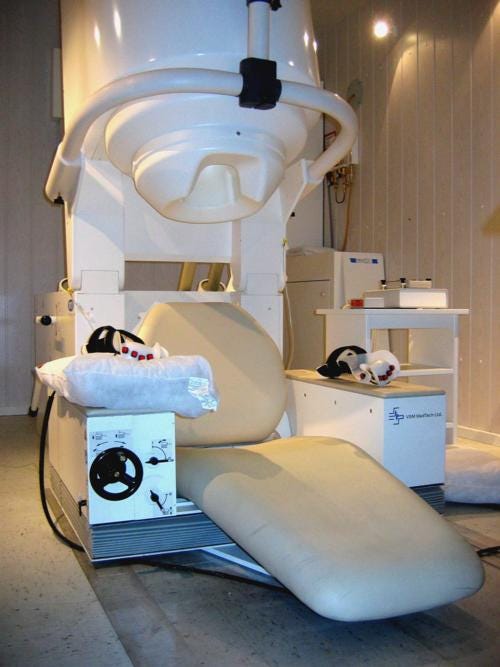

Traditional MEGs are about as compact and portable as MRIs. Which is to say, not very much.

MEGs consist of 300 SQUIDs spanning the subject’s head.

MEGs are a marvel of modern physics and engineering. But they suffer from many practical limitations:

Expensive: cooling to cryogenic temperatures requires liquid helium

Finicky: have to be mounted in a fixed array, this doesn’t account for variable head size of subjects

Signal degradation: the head needs to be thermally insulated from the ice-cold sensors, so a minimum 2cm distance is required, degrading signal strength

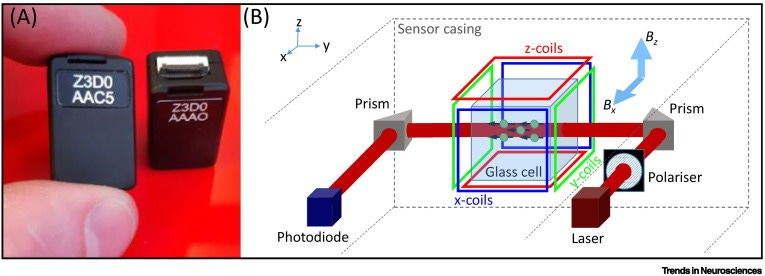

Luckily, researchers have made a version of MEGs that’s the size of LEGO bricks:

OPM-MEGs

They call ‘em OPM-MEGs.

Nerdsnipe: Lightbending

Let’s talk about light!

Visible light is made up of waveforms of varying wavelengths. (These waveforms have distinct colours.)

The speed of light changes based on the medium it is in

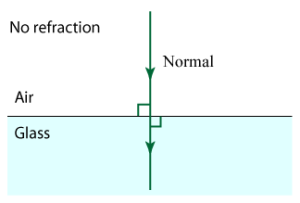

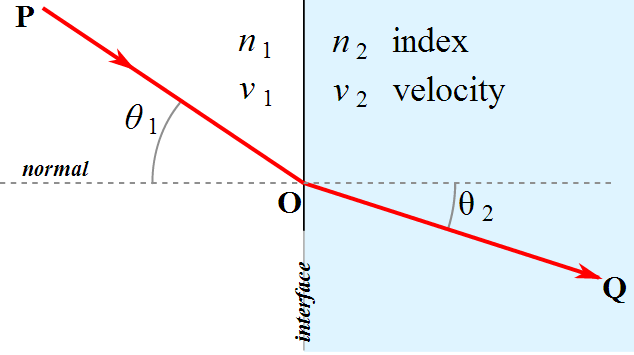

When light travels from one medium to another, the angle at which it enters determines how much it is “bent”

To understand why point #3, consider light travelling from air to water with no bending.

Versus when it is at some angle theta_1 > 0:

When light enters a medium at an angle, different parts of the waveform enter at different speeds:

This bending of light is known as refraction. This is also why prisms are triangular, and not rectangular. The latter would accomplish nothing.

We can use prisms to split light into its constituent parts:

Diffraction grating is superior to refractive prisms and what researchers actually use today, but they accomplish the same goal: splitting light into parts.

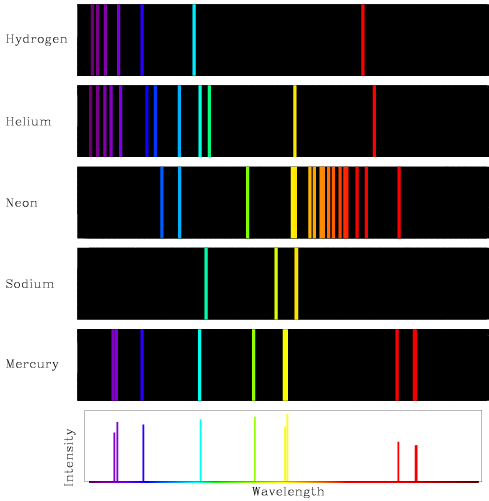

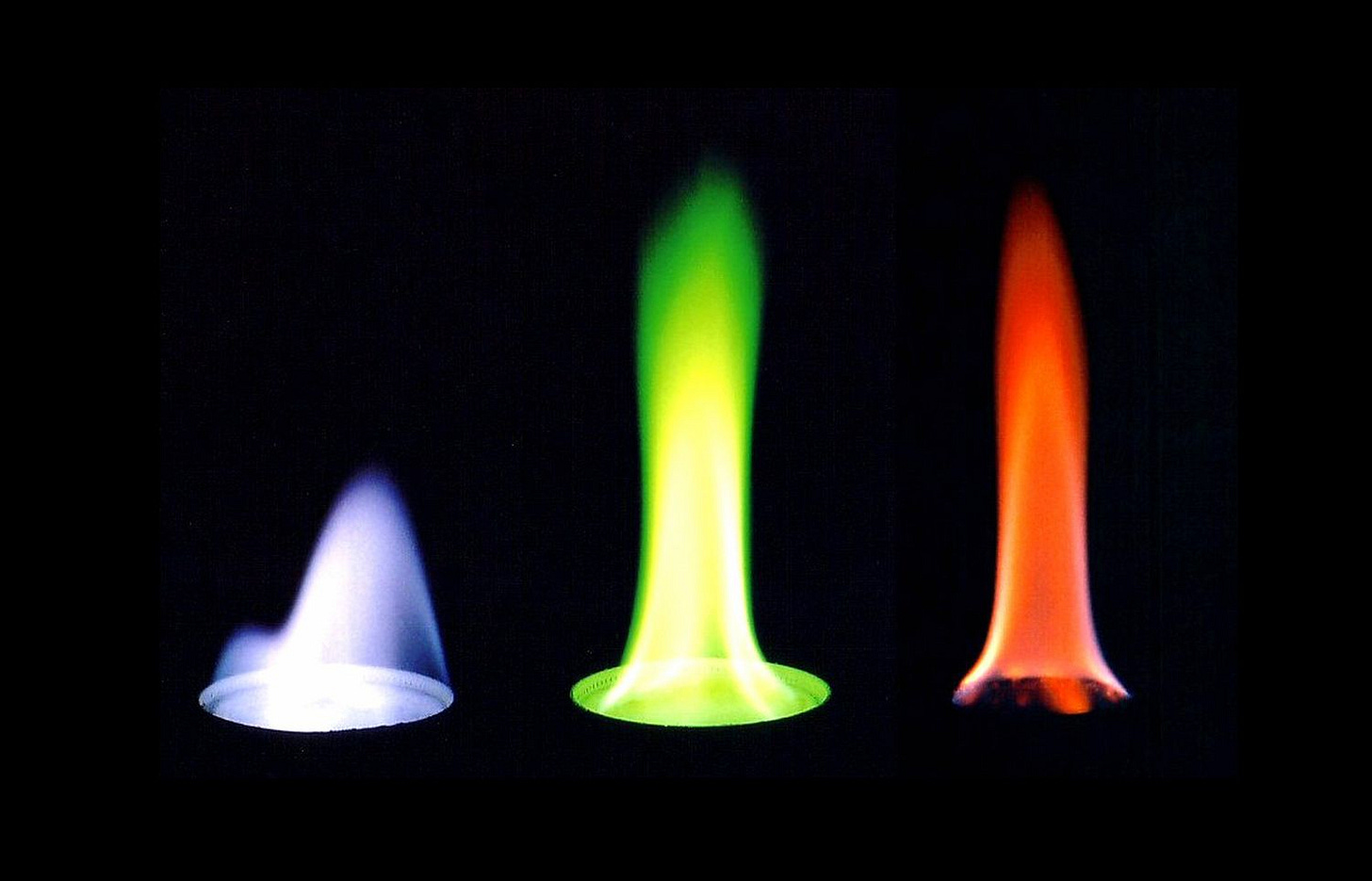

When you heat an element or compound, it emits light (electron → photon, opposite of Photoelectric effect):

Each element has a unique emission spectrum:

You know how I said heating elements produce light?

You can achieve the same effect with electric or magnetic fields. Pseudo-intuition for why this should be true: conservation of energy.

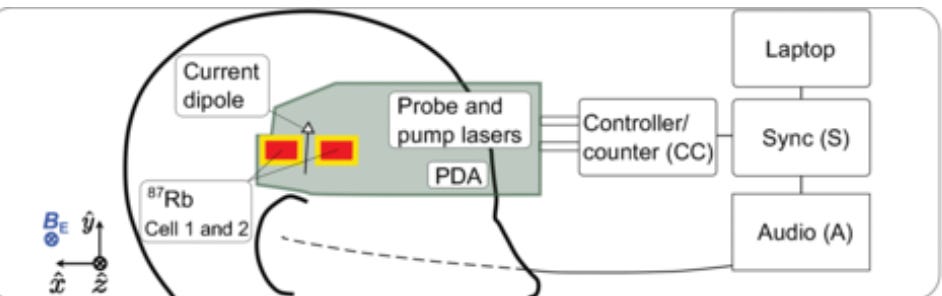

So back to OPM-MEGs. The “OPM” stands for “optically pumped”. These devices leverage the splitting of light in the presence of a magnetic field.

The periodic table is a useful taxonomy for elements:

The first column in the table is known as alkali metals.

These guys are easily excitable (one valence electron).

It’s the only “family” in the periodic table with each member producing a distinctive flame.

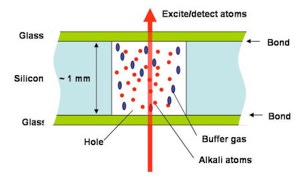

So we use alkali metals in OPM-MEGs - rubidium (Rb) being the most common choice.

The alkali metal usually comes in a sandwich known as a “vapour cell”.

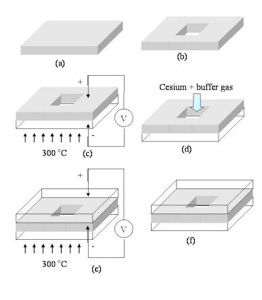

Nerdsnipe: Vapor Cells

How to make a vapour cell:

(a) Grab a silicon (Si) wafer. We like silicon

(b) Etch a cavity using photolithography techniques (which is why Si is used)

(c) Apply heat and electricity to bond the silicon to glass. We want a controlled environment (temperature, pressure).

(d) Add alkali metal with a buffer gas

(e)-(f) Do the other side

Voila!

OPM-MEGs overcome the fundamental limitations of SQUID-MEGs:

Cheaper: No need for cryogenic cooling

Adjustable: no need for a fixed sensor array

Accurate: no need for a thermal insulation layer, so close to the brain

Also, unlike EEG headsets, where you have to individually apply gel to each electrode, OPM-MEGs are faster to set up!

OPM-MEGs are really sensitive.

And magnetic fields are everywhere. Earth has a magnetic field between 22 and 67 microteslas (100-1000x weaker than a fridge magnet).

How do we tune out the noise? Typically through magnetic shielding, where metals with high magnetic permeability are arranged to maximize the signal detection of OPM-MEGs.

But this is too cumbersome. We want something that’s portable.

A magnetic field, B, consists of the signal, and a noise term.

The Earth’s magnetic field doesn’t vary too much over short distances. If we measure two magnets a few centimetres apart, they’ll have basically the same noise!

Or

If we just measure the difference or “gradient” between the two fields, we no longer have to worry about the local magnetic noise!

This is basically a differential amplifier (like the op-amp we saw before).

Congratulations, you just invented the magnetic gradiometer.

By placing two magnetometers like 3 cm apart, we can get really precise measurements in an ambient, outdoor environment!

I think portable magnetometry is very exciting. You can read the full paper here.

Sonera Magnetics is also working on portable magnetometers.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

What if we used a giant magnet to look inside the brain? That’s the principle of operation of MRI machines.

The reason magnets work at all is because everything is made up of charged particles.

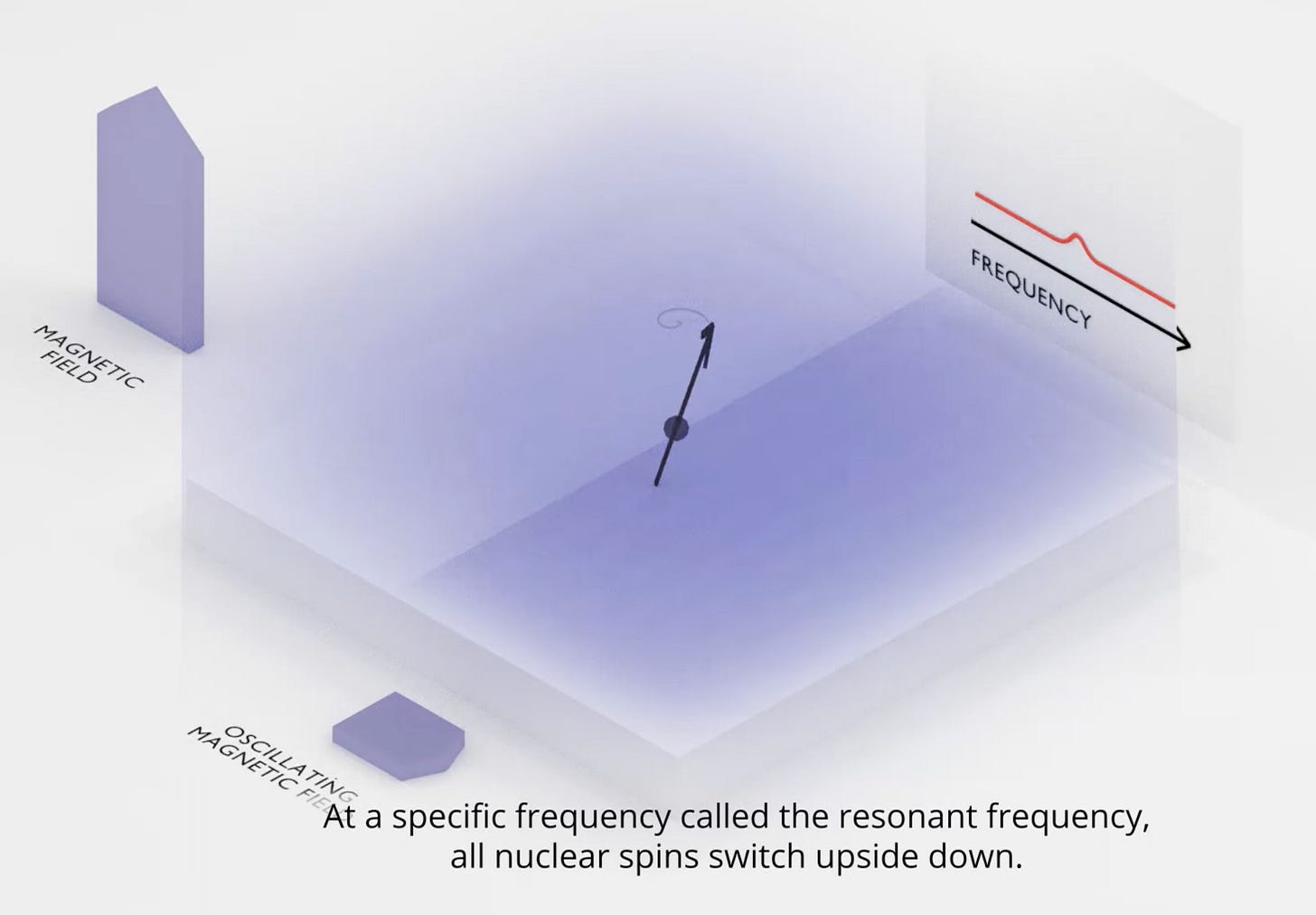

Nerdsnipe: Nuclear magnetic resonance

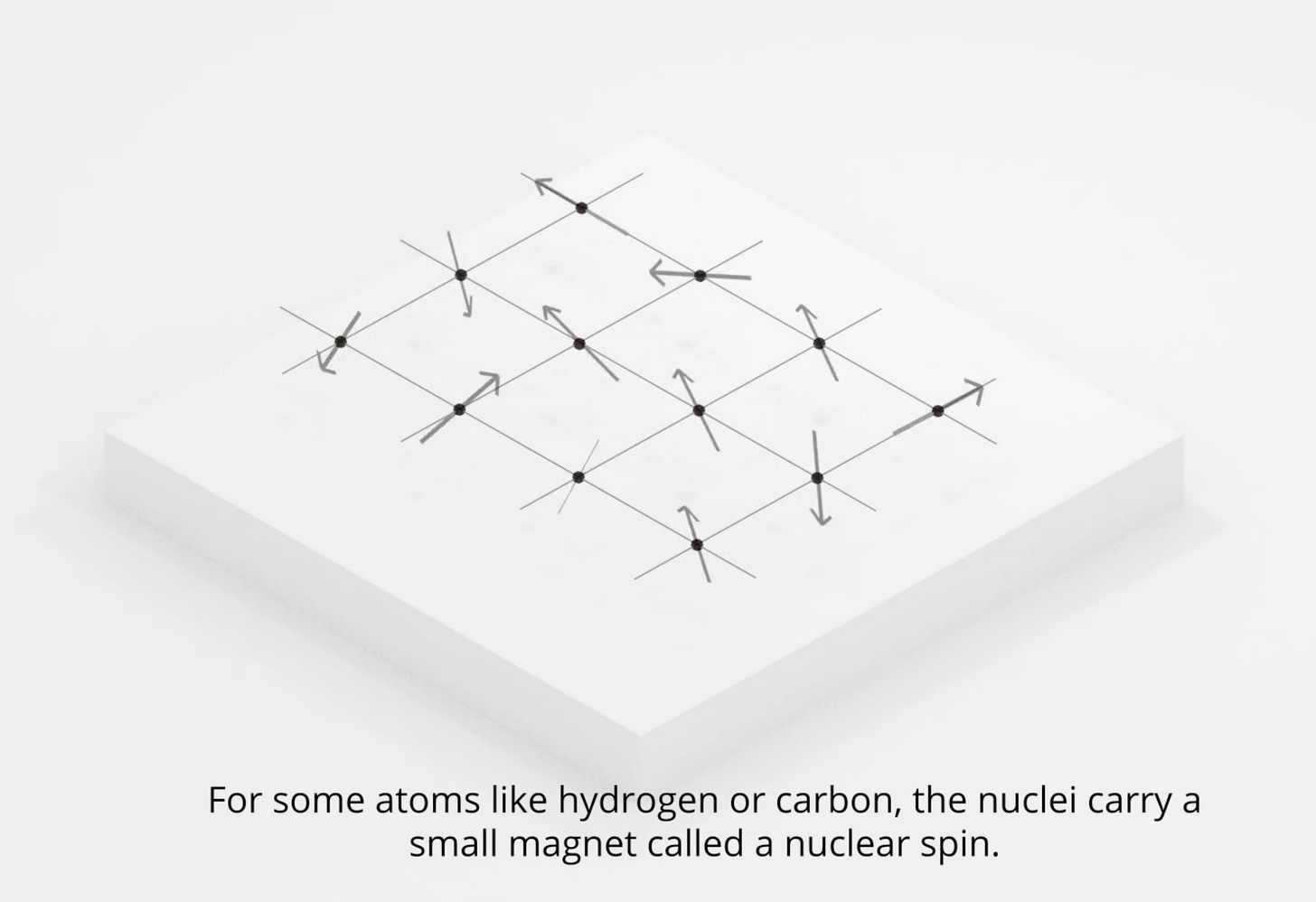

We are all made of atoms.

And every atom is a tiny magnet.

In 1946, physicists at Harvard and Stanford discovered that each nucleus has a specific frequency at which it is able to absorb energy. This “natural” frequency is modulated by the strength of the magnetic field applied to it.

This is the core operating mechanism of MRIs. It’s a simple 3 step recipe.

Step 1: Create a strong magnetic field, B_0, to align all the nuclei

Step 2: Apply a weak, oscillating field, B_1, to perturb the spin of the nuclei. The oscillation helps narrow in on the resonant frequency.

Step 3: This perturbation causes the nuclei to emit EM waves, as it returns to its starting position. This “precession” is what MRI machines detect.

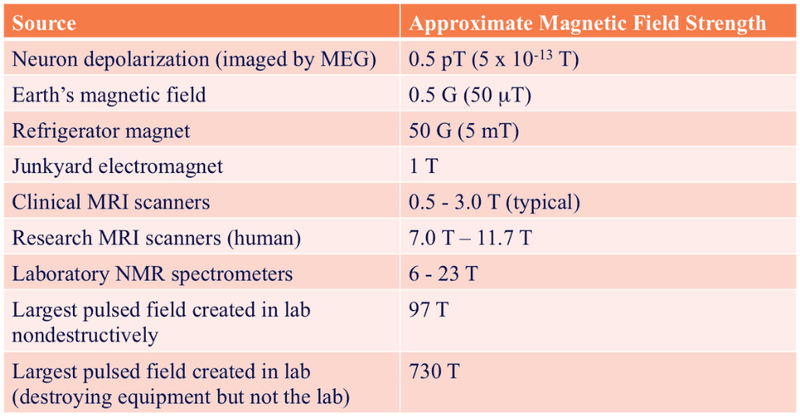

MRI machines are made with “super magnets”.

To give a sense of just how powerful these magnets are:

The typical MRI magnet (0.5-3.0 T) is 200x stronger than your average fridge magnet (5 mT). Because of the brute strength of these machines, metal objects are an absolute no-no. Scissors, pens, and stethoscopes turn into a whirlwind of flying projectiles if not removed before entering the operating room.

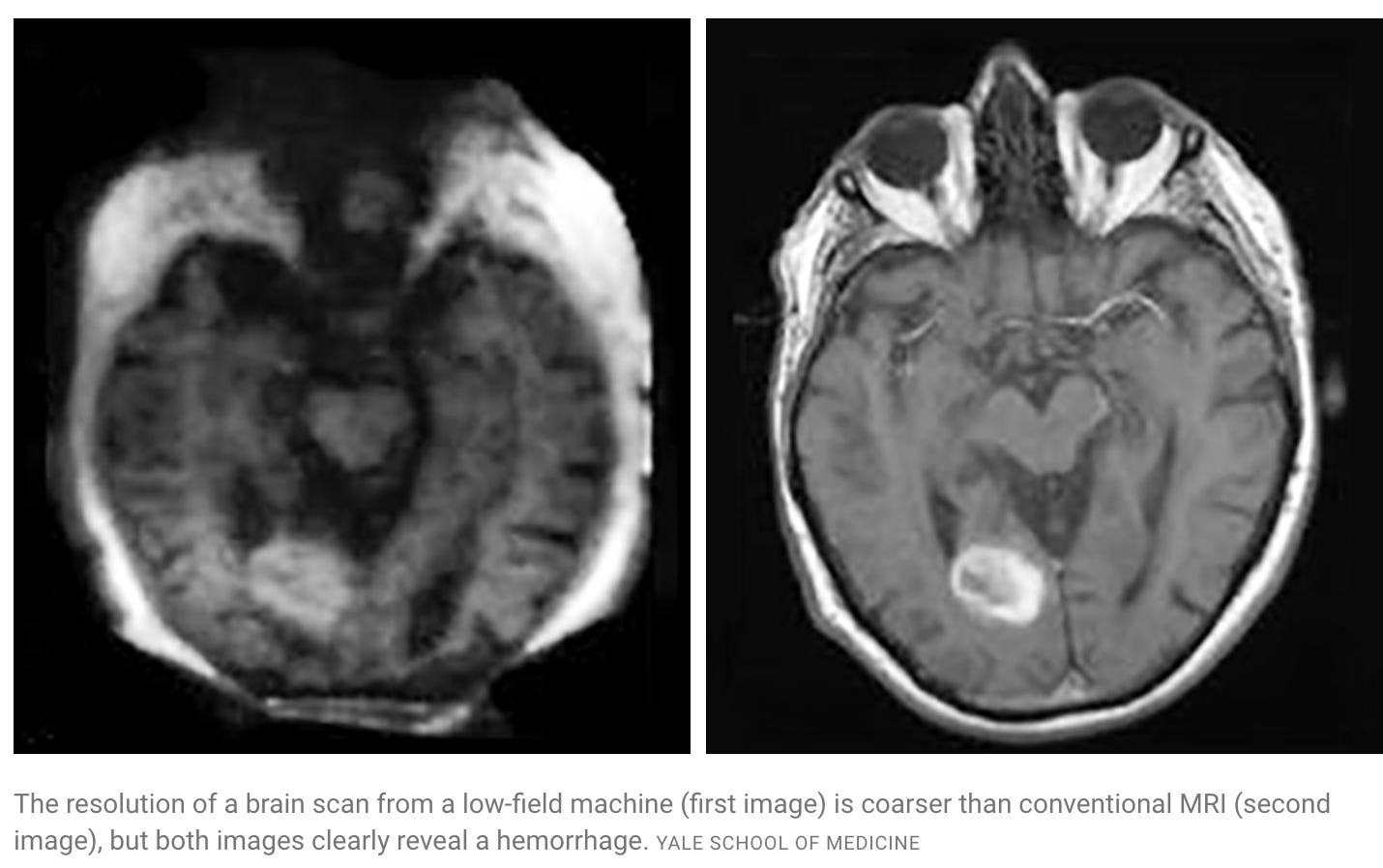

This matters for accuracy:

The 3T image is much sharper than the 1.5T one.

Hyperfine is building a more mobile MRI machine.

It’s small enough to be wheeled into a hospital room. Not as powerful, but advances in signal processing mean we still get MRI scans with utility!

Now, the MRI machine we’ve described so far is static. It gives us a high-resolution structural image of the brain, but has no temporal component.

fMRI

You have likely heard of fMRI. The f stands for functional, and it is the predominant imaging “sequence” used with MRI machines.

The central insight of fMRI is that blood follows brain activity. The human body releases more oxygen-rich blood to active neurons, and the differences in oxygen can be imaged with the NMR technique we discussed earlier.

So fMRI gives us a dynamic picture of brain activity over time. Only one caveat: the machines are still ginormous, and require patients to be immobilized. This makes them impractical for everyday consumer use cases.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS)

What if we could have the form of EEGs but the function of MRIs?

Enter fNIRS.

fNIRs use light (doesn’t mean visible light!) instead of magnetism.

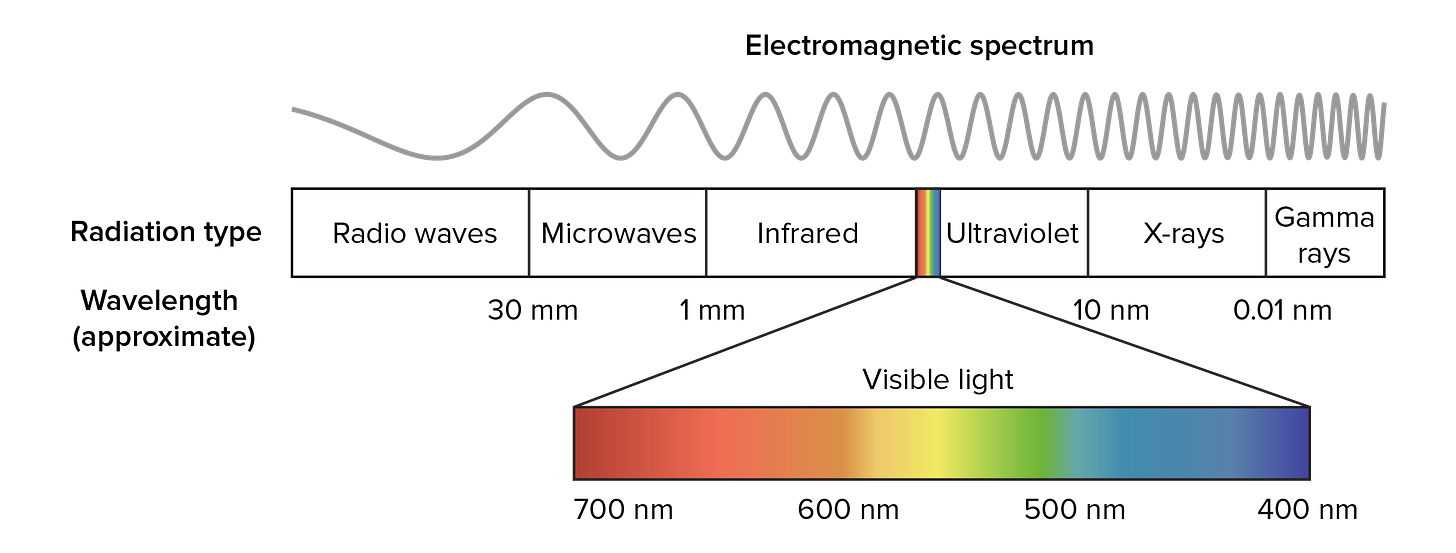

Light is a wave, and spans a spectrum of wavelengths.

Light absorption varies by tissue type.

Hemoglobin (Hb) is the protein in red blood cells that give them their characteristic red color. Blood absorbs light readily at short wavelengths.

At long wavelengths, water in cell tissue absorbs light.

The optimal window for light to penetrate tissue is in the 650 to 1350 nanometre range, which lies within the near-infrared portion of the spectrum.

fNIRS can penetrate the brain a few centimeters deep. This goes past the cerebral cortex, which is between 1.0-4.5mm in depth. But this isn’t anywhere near enough to probe deep into the brain.

Example: The Kernel Flow is a consumer fNIRS headset.

Optical methods are fundamentally constrained by light scattering. Embedded devices could solve this problem; shifting the challenge from waves to power electronics.

So, what’s stopping us from having minimally invasive nano devices in the brain?

For embedded devices to be practical, the power demands would have to go down by several orders of magnitude. I recommend Section 4.3 of Marblestone at al (2013) for a deeper dive.

Molecular Recording

Why try to engineer man-made systems to survive in a biological environment, when evolution has created molecules that do so already?

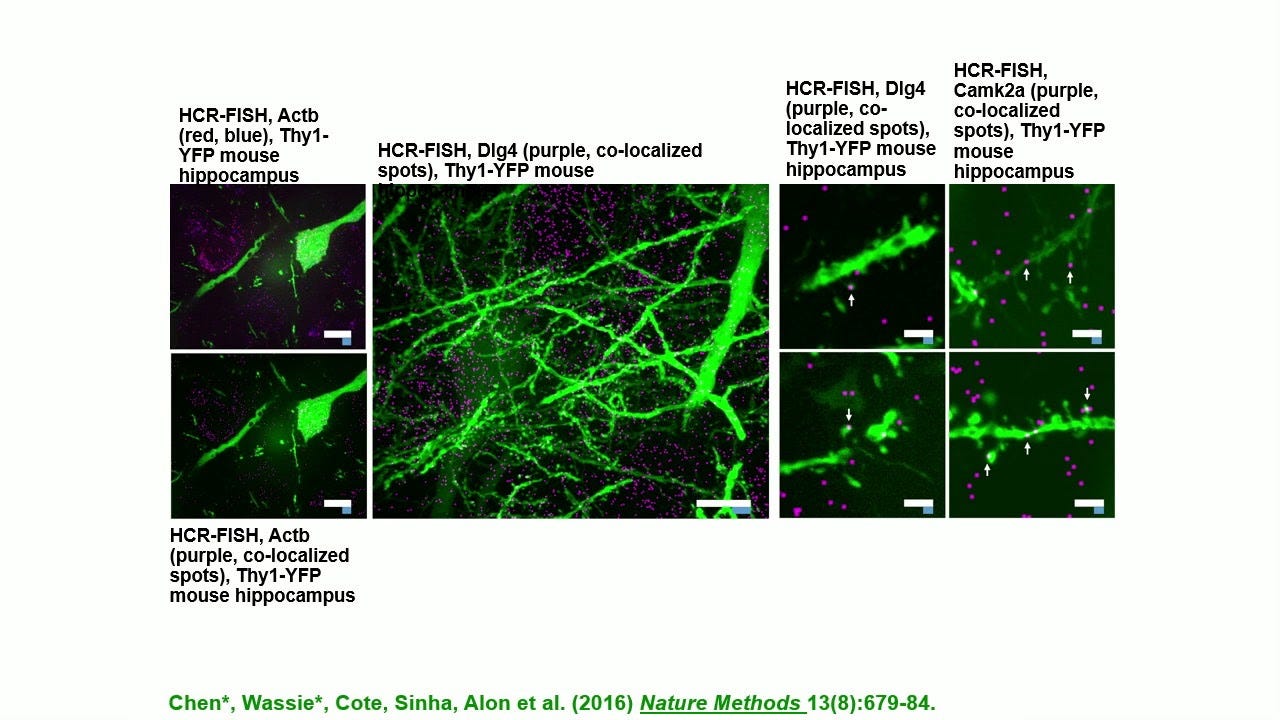

Enter DNA data storage. Molecules can be genetically encoded to record proximal cellular activity.

DNA is assembled by a protein (“polymerase”). We can genetically engineer a polymerase that is given a template DNA strand but is sensitive to voltage (deviations in ions, such as Ca^2+). Thus, the rate of error or “misincorporation” in the polymerase’s DNA writes is a linear function of fluctuations in voltage, and can later be read by DNA sequencing. This idea proposes a “molecular ticker tape”.

I don’t trust my bio knowledge to pontificate about this so I suggest Section 4.6 of Marblestone et al (2013).

Connectomics

Connectomes allow us to emulate the entire nervous system of an organism.

This gives us digital brains. Leaving aside the possibility or desirability of mind uploads, this is awesome for research. You can iterate much faster when you have an accurate, complete model.

What connectomes has humanity built so far?

We have one for the fruit fly (~200,000 neurons).

E11 Bio is working on mapping the mouse brain, as an important milestone in building up to the human brain. The brain of a mouse is ~6500x larger (in neuron count I’m guessing) than that of a fly’s.

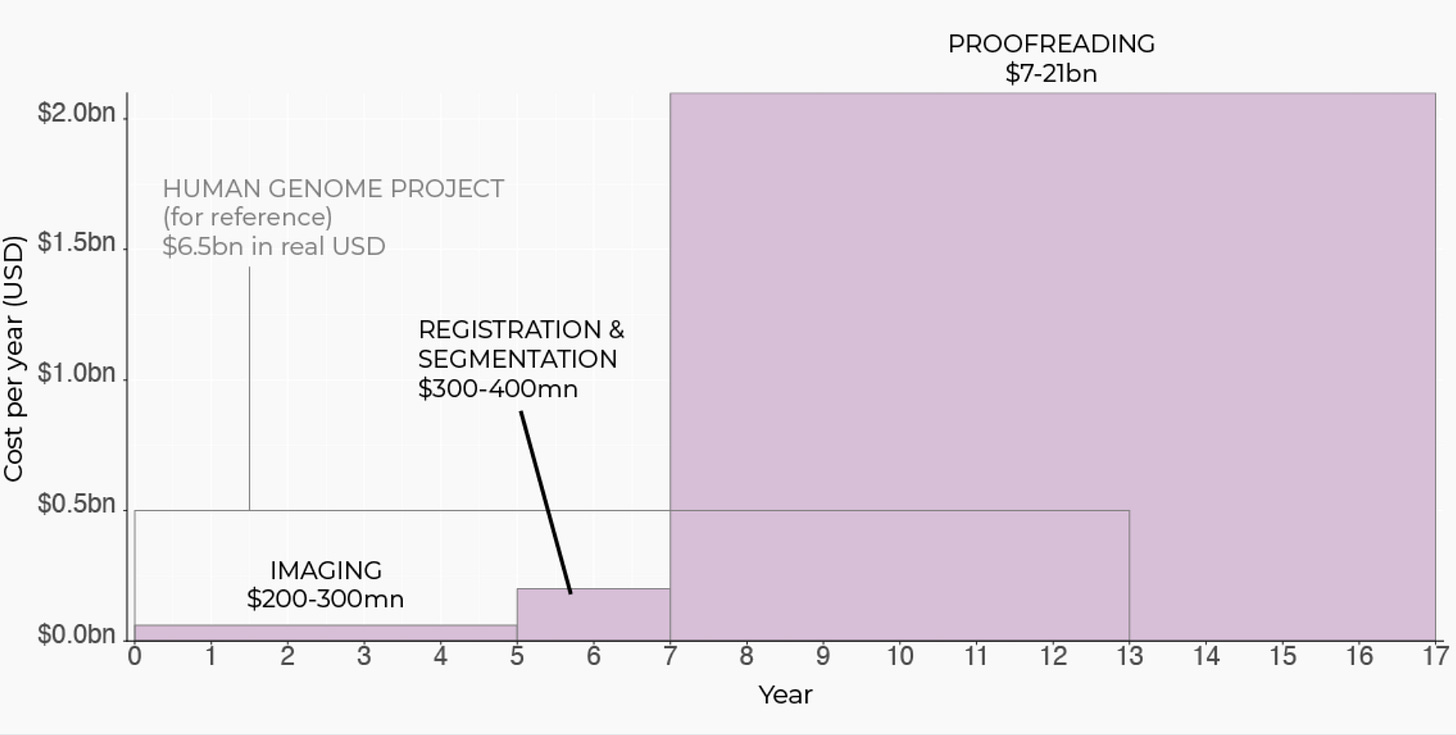

This is several orders of magnitude to scale. It turns out that the biggest bottleneck to scanning brains with current methods (electron microscopy) is human beings.

The E11bio pipeline, PRISM, consists of three steps:

Protein cell barcoding

Expansion microscopy

AI models

Step 1: Protein cell barcoding

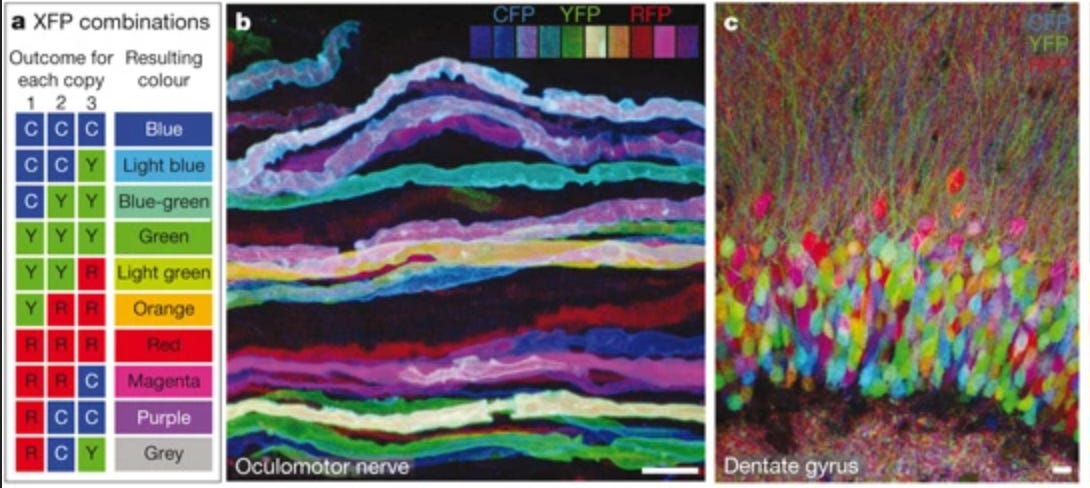

In 2007, a team at Harvard decided to paint. In the mouse brain. Some naturally occurring proteins are fluorescent. We can use genetic engineering to extract these and express them in other organisms.

Brainbow uses different mixtures of red, green, and blue to mark neurons with distinctive colors.

PRISM extends this to express way more colors by using 18 different protein tags, each viewed with a different color channel. Each tag can be either on/off, giving 2^18 = ~250,000 combinations. In principle, this can be extended to millions of combinations too by adding more color channels and corresponding tags.

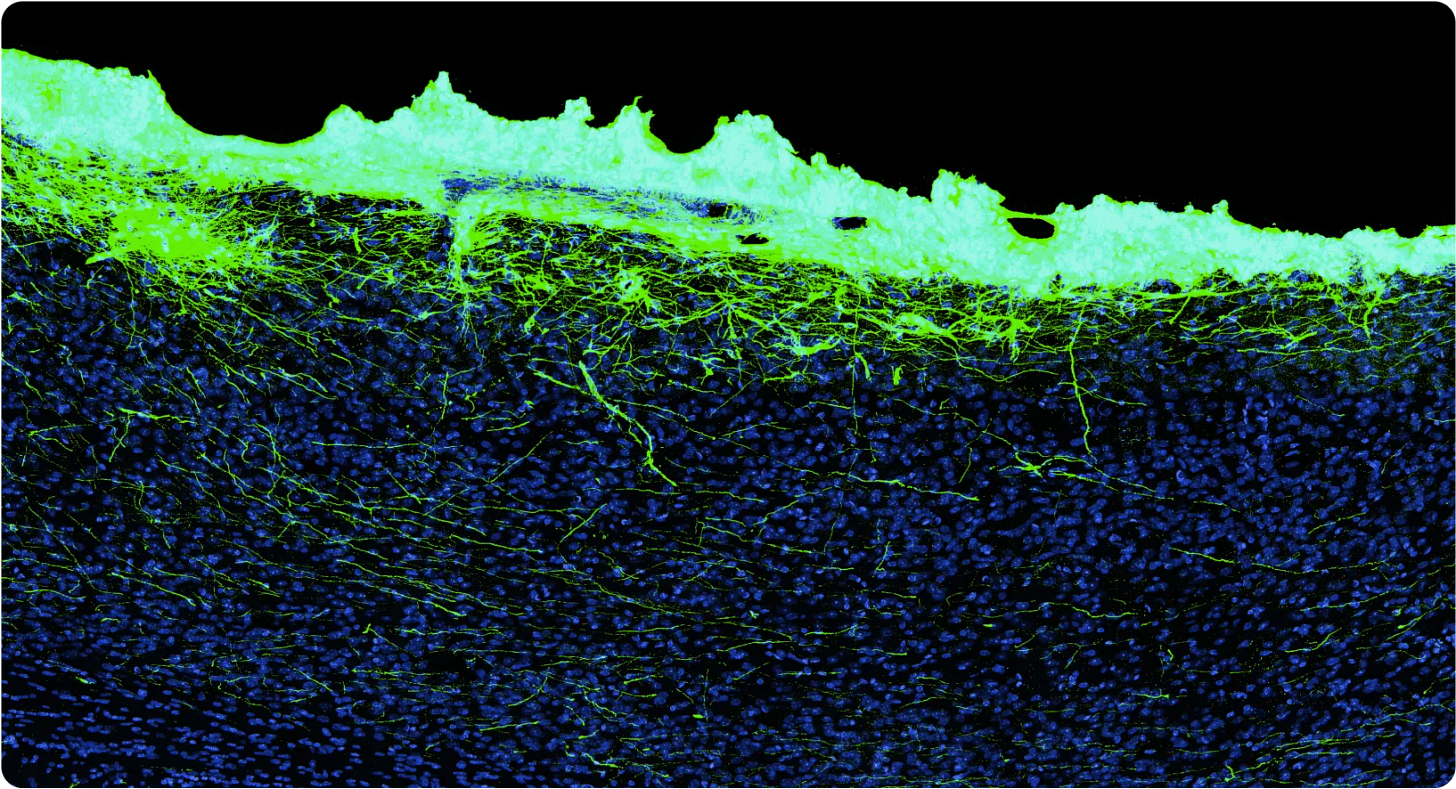

Step 2: Expansion microscopy

Next, expansion microscopy is used to detect each one of the separate information channels.

Step 3: AI models

The distinctive visual biomarkers give E11 a lot of rich data, and now they can train very capable image segmentation models.

Full-waveform inversion (tFUS)

Geophysicists have a problem.

They want to understand the composition and structure of terrain, based on limited data from satellites.

What do?

Wouldn’t it be sick if we could send sound waves, see how they’re transmitted/reflected etc and understand what kind of physical structure we’re looking at? We just discovered “full waveform inversion” (FWI).

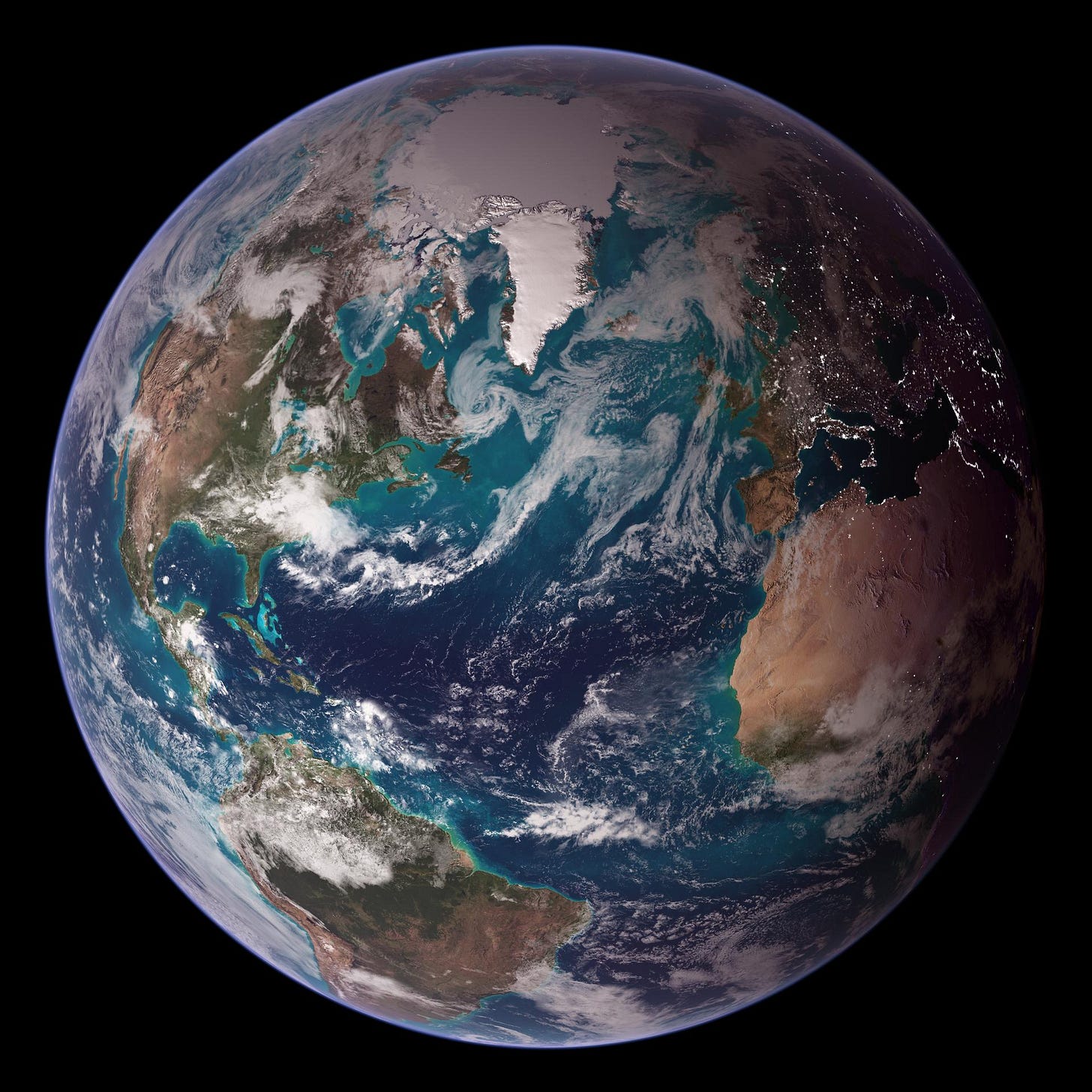

But you know what else kinda looks like a globe?

In later sections, we discuss ultrasound’s tremendous potential for writing to the brain. With FWI, we can read the brain using ultrasound!

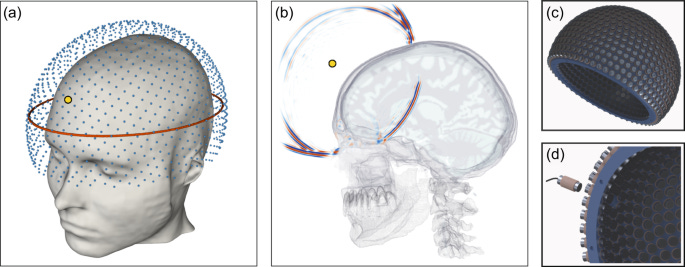

The idea is to cover the entire sphere by placing 1024 transducers in a cap. Each transducer is both a source and a receiver. Each transducer sends out a pulse, and has every other transducer record the energy. Even allowing for reverberations to dissipate first, the entire process of recording takes about 2 seconds!

Here’s a really cool video by the authors on wave propagation within the skull:

Writing to the Brain

EEG, MEG, fMRI, fNIRS - most imaging techniques are read-only.

Notably, tFUS is exciting because it promises deep brain write access using ultrasound.

Focused Ultrasound (FUS)

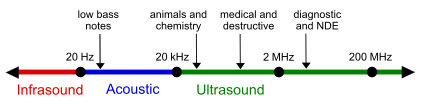

In standard room temperature and pressure with air as the medium (i.e. default settings), sound tends to have longer wavelengths than light. This means sound waves tend to scatter way less.

Enter ultrasound. Fry et al in 1958 were able to temporarily “turn off” activity in a targetted region deep inside a cat’s brain. Humanity had figured out how to neuromodulate - turn on/off brain regions — on demand. Also, ultrasound seems to be harmless to brain tissue.

Fry’s approach was to drill a hole in the cat’s skull, and this is the standard for brain surgery patients today.

A recent paper by Rabut et al (2024) explores the use of a polymer-based replacement material for part of the skull that does allow ultrasound through (“acoustic window”).

Transcranial FUS (tFUS)

Experiments have revealed the parietal and temporal bones to be the most sound-friendly.

Now that we know which part of the skull suffers the least from attenuation, we can emit focused ultrasound accordingly.

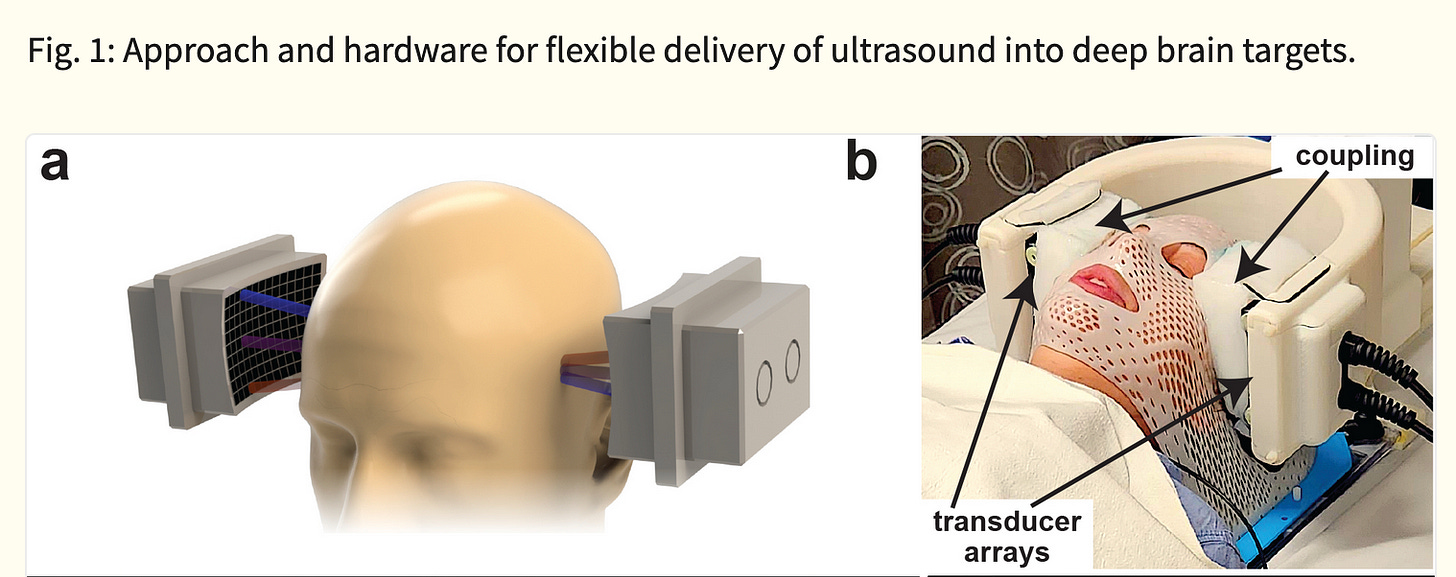

And that’s exactly what Riis et al (2024) do:

Ultrasound, being sound, consists of waveforms. We want to control these waves to finely control the intensity.

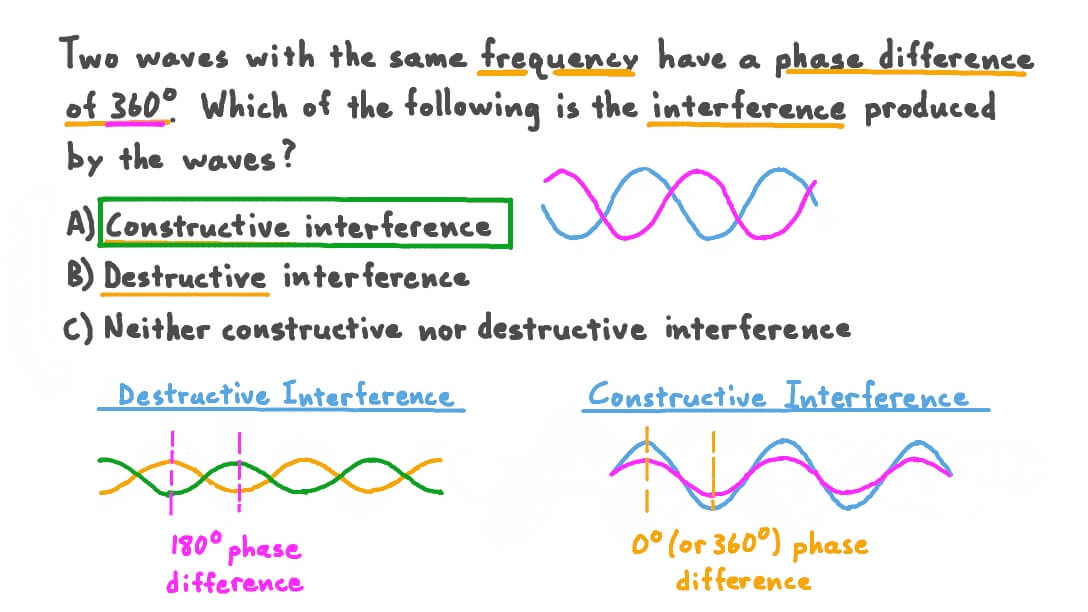

Constructive interference is when the waves have the same phase and combine to form a wave of greater amplitude. Destructive interference is the opposite.

The art of controlling waves to achieve high signal-to-noise is known as beamforming.

The tFUS device above, the SPIRE Diadem, consists of an array of ultrasound transducers. One of each of these arrays is placed on either side of the subject’s skull.

For coupling to the skull/brain, cryogel is used as an “acoustic window”.

SPIRE’s Diadem is in the midst of starting a Phase 3 trial for FDA approval.

What is a transducer, anyway?

Traditional transducer arrays are made of piezoelectric crystals (PMN-PT, in the case of the Diadem).

0. Piezo-electric crystal

“Piezo” is Greek for press. Piezoelectricity then is electricity generated via pressure.

When a force is applied to the crystal, it results in a displacement of the charge dipoles, and creates a resultant charge on the crystal’s surface. This surface potential can be measured.

Any mechanical stress can be measured as an electric charge.

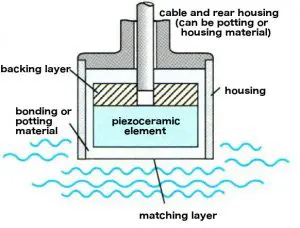

In practice, you need a few more pieces to go with the crystal:

1. Matching layer

Sound, when going from one material to another, is either transmitted or reflected. We want ultrasound to be transmitted. But if the impedance between two materials is high, sound is reflected back. The matching layer is chosen to have an in-between impedance to improve transmission. We can stack matching layers to further improve how much sound is transmitted!

2. Backing layer

Okay so we’ve added some matching layers, our sound is mostly going through. What of the sound that is reflected? The backing layer is made to be attenuative (i.e. really good at absorbing sound) so reflectant sound waves don’t interfere with the original forward signal

3. Housing layer

Just a wrapper for the electronics and materials

Cool, we know how a single element transducer is made.

Initially, people used naturally occuring crystals such as quartz because it occurs naturally.

Then, crystalline ceramics made in labs (first PZT, more recently PMN-PT)

But we can make way smaller devices.

What do computers, solar panels, and the human genome have in common?

Exponential growth for decades. And the root of this progress is advances in semiconductor fabrication.

These manufacturing and lithography techniques transfer to other kinds of miniature electronic and mechanical devices.

Ultrasound devices can be built to be way smaller.

Butterfly Networks has already built a portable ultrasound scanner for medical imaging. Now, they’re partnering with Forest Neurotech to build one for neuromodulation. Their first prototype, Forest 1, is a pocket-sized ultrasound device that has larger coverage than existing implants (e.g. Neuralink), and sits at the skull, making it less invasive than other probes.

We’ve discussed the mechanical effects of FUS.

Also we’re talking about low intensity focused ultrasound.

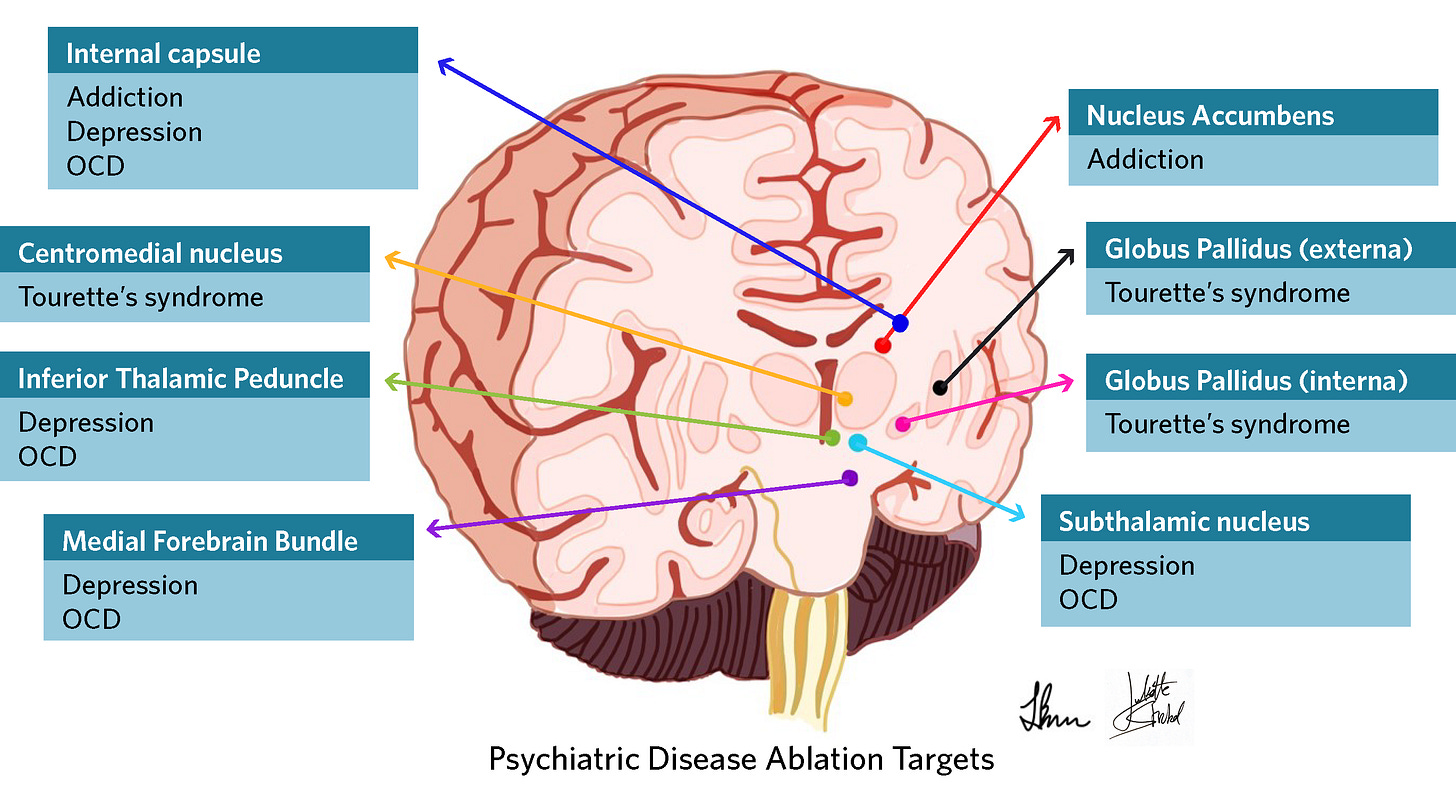

There’s also high intensity ultrasound, which can be used for surgery (thermal ablations).

How do they compare to orthodox surgery techniques?

Going back to the skull, there is exciting independent work by Hotter et al that improves on existing de-aberration algorithms for improving the signal-to-noise of ultrasound waves that pass through the skull.

How is ultrasound actually delivered to the brian?

Sonogenetics combines ultrasound with virals that inject genetic material into neurons, such that they respond to ultrasound.

Laser-induced has high spatial resolution, but is energy intensive

Nanoparticles

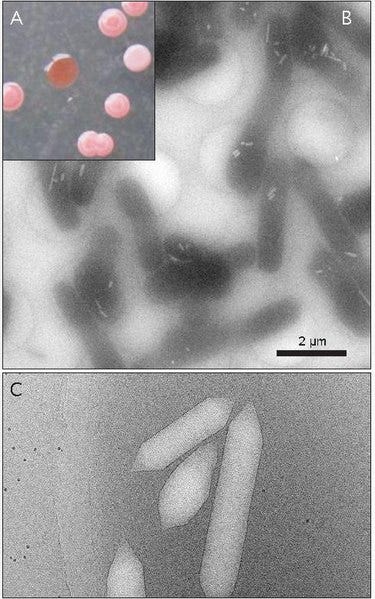

This paper uses nanobubbles for super precise ultrasound targeting.

Some microorganisms have “gas vesicles”, nanostructures that are impermeable to water, but permeable to gases.

In nature, these are used by said microorganisms for regulating their buoyancy in water.

Since they’re responsive to gases, we can hit them with ultrasound. The vesicle’ move, and their mechanical energy activates ion channels (“mechanosensitive”) in neurons. We can add fluorescent proteins and bam, we now have a super precise picture of highly localized regions anywhere in the brain.

This paper so cool idec it was in mice.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

If we can use the principles of electromagnetism to read from the brain, why not use them to write to it?

If EEG is for read access to the brain, tDCS is its write counterpart. Direct-current stimulation unfortunately also can’t go past the cortex.

Consumer product: Flow Neuroscience

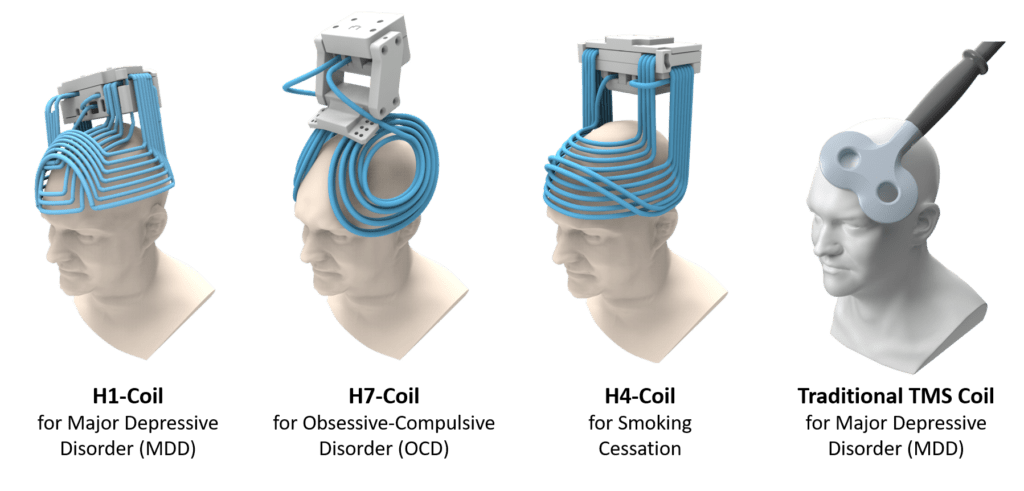

Similarly, TMS is the modulation analogue to MEG. You place a magnetic coil on the scalp. TMS traditionally doesn’t go into the subcortical regions of the brain.

However there is research into design for coils, such as BrainsWay Deep TMS™. These devices have received FDA approval for a range of addiction and mood disorders.

These can stimulate multiple cortical sites at once (“multi-locus TMS” (mTMS)).

The challenge is going past the cortex without invasive surgery.

Now, truly “deep brain” stimulation is sometimes invasive, such as this recent paper that restored the ability to walk in 2 human participants. This is a tremendous achievement, as is the work done by Neuralink.

Ed Boyden’s lab at MIT is a pioneer of precision neuromodulation. They wield electric fields and lights.

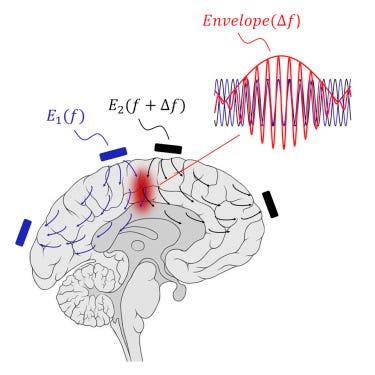

Temporal electrical interference

Neurons in the brain act as a low-pass filter (LPF) + rectifier. Electric fields with >1kHZ frequency are filtered out (LPF). High-frequency AC current changes direction too fast for the switching to be picked up by the neuron, but the lower frequency envelope is picked up (thus, the neuron acts as a rectifier).

This prevents the use of directly high-frequency electric fields to induce deep brain stimulation. But if we have two waves that differ by some small delta, we can take advantage of constructive interference and resonance!

Side note: funny how subtracting one thing from another works so well

This ingenious approach is called temporal interference and was tried out by Boyden’s lab in mice back in 2017. Seems like an exciting research direction (h/t Sarah Constantin).

The above suffers from off-target hits.

… Which is addressed to some degree in mice:

Biohybrid Interfaces

In principle, it’s possible to get a much deeper localized understanding by placing probes in the brain. That’s how Neuralink works.

Any invasive method destroys some amount of brain tissue (Butcher number). The tradeoff is worth it for serious injuries, but is not great for scaling.

That’s why most consumer approaches — ultrasound, fNIRS — rely on remote transmission through light or sound waves. They move into the realm of wireless connections and information theory.

But the Butcher number isn’t a law of physics, it’s a rule-of-thumb that is true until we (as a species) get better at neuro engineering.

If we could place our sensors right next to neurons, measurement becomes much easier.

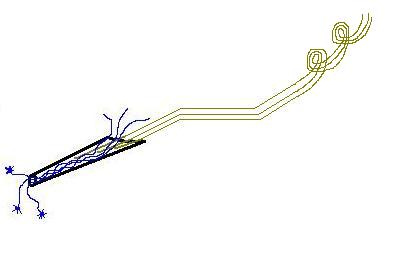

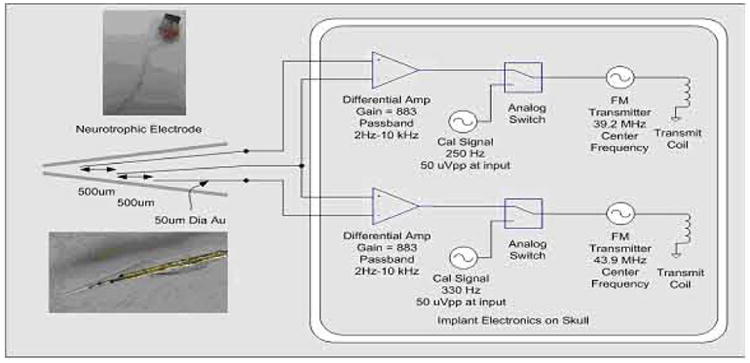

Dr. Robert Kennedy came up with the neurotrophic electrode in the 1980s. This consists of:

glass cone, coated with growth factor (-trophic) to encourage neurites (lil extensions from neurons) to grow through it

gold wires, conducting electrical activity from nearby neuronal axons, coated with Teflon for insulation

electronics, differential amplifiers to amplify the tiny voltages, and FM transmitters to send the signal remotely

Interlude: differential amplifiers

Noise cancellation is crucial for detecting small signals. That’s why differential amplifiers have two terminals; unwanted background noise should couple equally to both terminals, leaving only the signal we care about. Pictured below is an operational amplifier (op-amp).

Interlude: wave modulation

All of telecommunications is about sending waves.

The wave has an amplitude (A), angular frequency (w) and phase (phi).

If you want to send a signal, you can vary any of these, each with different tradeoffs. Broadly speaking, FM and PM are both angular modulation techniques, and we will be discussing FM today, and setting phi to 0.

This gives us:

FM gives you higher frequency waves that are more resistant to external noise (but go a shorter distance). AM gives you way more range but is more prone to corruption (thunder, birds cawing etc)

Anyway, back to our biohybrid electrode.

The wireless transmission helped prevent risk of infection from having too many wires going through brain tissue (“transdermal”). But it also meant that this couldn’t be embedded too deeply, because of the constraints of RF transmission.

So we have a device that is synthetic, yet lives in harmony with other neurons. Solarpunk type beat.

What happens if we scale this idea?

That’s what the team at science.xyz is trying to do.

Their approach is based on adding engineered stem (baby) neuron-like cells to the brain, and letting them connect with the existing neuron population.

The challenges to surmount here are non-trivial. Our immune systems are suspicious of foreign cells. You can’t just add random stem cells and expect them to survive in the brain. But we can genetically engineer them to not trigger a strong immune response (hypoimmunogenic) by grafting cells from the patient’s body (allogeneic).

Super excited to see where this line of work goes.

x-Genetics

Optogenetics

If the mitochondria are the powerhouse of the cell, proteins are its workhouse.

Some proteins are sensitive to light. We have such proteins in the retina. Boyden realized that we could genetically embed light-sensitive proteins (from algae or bacteria) into neuronal bodies!

This gives us observability for the brain.

This is unfortunately invasive and to my knowledge has only been tried on mice. So we are a bit away from consumer adoption. But very cool nonetheless!

Magnetogenetics

Optogenetics is limited by light scattering.

But what if we could use remote controlled magnetic fields to simulate cellular functions?

Magnetogenetics, baby. I haven’t looked at this too deeply but this looks like a good review paper.

Chemogenetics

Other work has explored the usage of gene therapeutics for neuromodulation.

Part 3: Applications

What are the problems of neuroscience?

What isn’t? Milan has a list.

The promise of ultrasound is huge. Mood disorders, epilepsy, blissful states of consciousness — the floodgates would open. Understandably, there’s a lot of hype and startups betting on it.

But how strong is the present evidence?

Let’s take a look at the clinical data and commercially available devices for the most promising neurotechnologies.

Chronic Pain

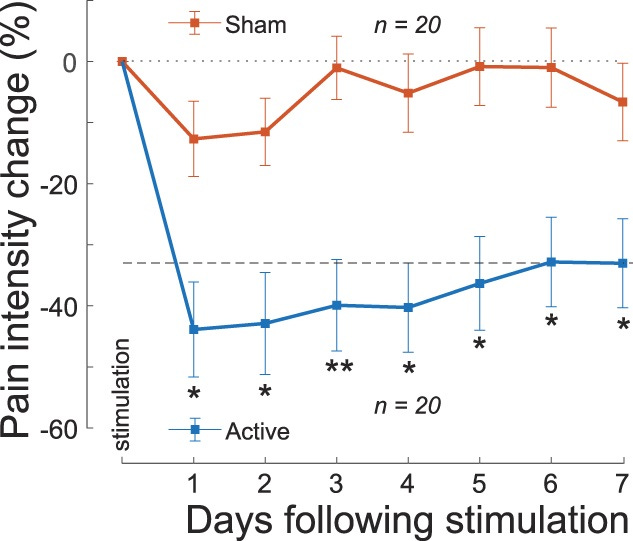

Riis et al used their tFUS headset to reduce chronic pain in subjects. A single 40-minute session of administering focused ultrasound resulted in a significant reduction in chronic pain that lasted for a week

Attune Neurosciences is doing a study and is looking for volunteers. Could be you.

Depression

BrainsWay Deep TMS™ was FDA approved for treatment for patients with depression in 2013.

Stanford’s SAINT protocol, which also uses deep magnetic stimulation in the brain, cured depression in 22/29 participants with treatment-resistant depression.

OCD

A 2019 study at Sunnybrook Hospital of 12 patients found that 50% of patients (so, 6 people) improved better “quality of life” after ultrasound treatment.

Addictions

BrainWay’s device was approved for smoking cessation in 2020. There’s a study, but it’s (partially) funded by BrainsWay, so take that as you will.

ADHD

There are many EEG headbands claiming to cure ADHD. At least, that’s what I overheard at a neurotech meetup in SF.

One example is Neurode, which is a headband that tingles your prefrontal cortex (PFC). Would love to talk to anyone who’s tried it lol.

Lucid Dreaming

Prophetic is building a headset for lucid dreaming on-demand: I have it on good word that they use a single transducer element targeting the right frontal gyrus.

Meditation

SEMA Lab performed a tFUS enhanced 10 day retreat alongside meditation luminary Shinzen Young. The team, led by Sanguinetti et al, seem to be using a single element transducer as well.

Focus

Early days, but this study (n=9) noted subjects’ enhanced sensory discrimination with tFUS.

Preference modification

In mice, so take it with a grain of salt but:

“... When the researchers delivered ultrasound stimulation to the cerebral motor cortex in mice, they observed significant improvements in motor skill learning and the ability to retrieve food.”

Part 4: What’s Next

What To Work On

If you want to make progress on frontier neurotechnology, but don’t have an agenda of your own, here are some teams you could join.

Electrode Implants

Neuralink continues to do very important work (e.g. vision for the blind, mind-controlled computing for quadriplegics)

Science.xyz is working on bio-hybrid interfaces

Connectomics

E11Bio is an FRO working on using molecular markers, a more scalable approach to building the first mammalian connectome (of mice) than slicing a brain laterally

Ed Boyden’s lab at MIT is working in this space

tFUS

Nudge (by Quintin Frierichs and Fred Ehrsham) are working on ultrasound

Forest Neurotech is working on an ultrasound device in collaboration with Butterfly Networks

tFUS Society + Neurotech@Berkeley is working on Project Sonus, full-waveform inversion imaging of the brain. (They also host monthly meetups in the Bay Area if you’re interested!)

New ideas

There’s a lot of room for interdisciplinary folks with experience in electrical engineering, synthetic biology, and any number of fields in between to work on BCIs.

One idea I find compelling is that of modality cocktails, combinations of existing tech that overcome limitations. Examples follow:

Acoustoelectric effect

Ultrasound changes the conductivity of materials, thus interacting with surrounding electric fields. This is the “acoustoelectric effect”.

EEG has really high temporal resolution but poor spatial resolution. Ultrasound has high spatial precision. The acoustoelectric effect allows us to combine both.

This is what Childerhose et al explored in Brainhack 2024:

Spectral hole burning

This Twitter thread proposes combining spectral hole burning with ultrasound modulated light to build BCI. I don’t think anyone has tried this yet.

The idea is:

Focus light aka laser into the brain

Focus ultrasound on some tissue

The ultrasound induces a frequency shift in the light around the tissue region

Light exiting the brain now has a modulated and unmodulated component

A cryogenically cooled (i.e. negligible molecular vibrations), which had a “hole” burned to match the frequency of the ultrasound-modulated light, acts as a filter, only letting the modulated light pass through

Incrementally move the ultrasound focus, to build a high-res map of the brain

“ Consideration of analogies and synergies between fields suggests a combinatorial space of possibilities…Electrical or acoustic sensors could be used with optical [345] (e.g., fiber) or ultrasonic readouts and power supplies. An MRI machine could interact with embedded electrical circuits powered by neural activity [346]. Linking electrical recording with embedded optical microscopies or other spatially-resolved methods could circumvent the limits of purely electrical spike sorting. Optical techniques such as holography or 4D light fields could generalize to ultrasound or microwave implementations.” - Marblestone et al (2013)

Summary

I tried pretty hard, but there’s too much happening in neurotechnology for one dude to keep up with it. If I missed some nuance or you find something else that’s cool, do comment, I’d love to chat with you.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Raffi Hotter for fact checking some of my claims, and pointing me to further resources. Also, thanks to Adam Marblestone and Sarah Constantin for their many informative blogposts on neuroscience.

Thank you to Samia Tasmim for her help in editing this piece. Also shout out to Ricky Mao, Eden Chan, and Jackson Mowatt Gok for their feedback on early drafts of this post.

P.S. If you enjoyed this article, smash that subscribe button:

I wanna be like you when I grow up

amazing as always